Central Park: A Research Guide

Table of Contents

Introduction

The history of New York’s Central Park is inextricably linked with the social and cultural history of the City; the history of the park movement in this country; the birth and evolutions of the professions of landscape architecture, city planning, and urban park management; and ever-changing notions about recreation, democracy, and the role of public space in relation to both. Inquiry into the Park’s more than 150 years of physical, social, natural, and cultural history — from those who seek to learn from it and those who seek to care for it — is constant.

Central Park: A Research Guide (2016 Version)

Since 1980, Central Park Conservancy has worked to restore and manage the Park. This effort has constantly involved exploring and seeking to understand its various historic layers. As a result, Conservancy staff have become well-versed in the numerous archives, databases, and books that illuminate its landscapes and history. These can be found in many institutions — a variety that reflects the Park’s breadth of influence — including the Library of Congress, the New York City Municipal Archives, the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The fact that this information is spread across the city, and now, across the internet, can be a challenge for researchers.

The Conservancy prepared this document to support and encourage continuing scholarship about the Park. This guide shares our decades of experience researching the Park and reflects the goals of the organization to maintain and protect the Park as a scenic retreat from urban life, and also to share the history and significance of this extraordinary public space.

The research material described in this guide is organized into several broad categories. Within each category, specific resources and collections are described, and the key location(s) where researchers may find them are referenced. The end of this document includes some appendices, including a timeline of Central Park history, brief biographies of important figures in Central Park history, and, for scholars who would like to access the Conservancy’s archives, the Conservancy’s research policy and inquiry form. The guide was completed in August 2015 and is updated periodically with new resources and updated hyperlinks.

The Mission of Central Park Conservancy

The mission of Central Park Conservancy is to restore, manage, and enhance Central Park in partnership with the public.

Central Park Conservancy aspires to build a great organization that sets the standard for and spreads the principles of world-class park management—emphasizing environmental excellence—to improve the quality of open space for the enjoyment of all.

Central Park Conservancy is committed to sustaining this operating model to provide a legacy for future generations of park users.

Cover of Guide to Central Park, New York: A. O. Moore and Company, 1859

Bibliographic Material

An extensive amount of written material dealing with Central Park has been published in the course of its more than 150-year history.

While the works cited here are by no means exhaustive, an effort has been made to identify the books that focus on Central Park and will be of greatest use to researchers. They are divided into categories that reflect some of the main areas of interest in the Park, including general history and natural history; biographies, memoirs, and papers; and guide books and descriptions.

Much of this material is available in a number of research libraries. The New York Public Library contains a significant number of these titles. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, part of Columbia University, also includes many of these titles, though access is somewhat restricted. Some of the guides written and published in the nineteenth century are available on the internet in archives such as Google books and the Internet Archive.

General Park History

The following books provide an introduction to the history and landscapes of Central Park and background on the urban parks movement.

Brenwall, Cynthia S. The Central Park, Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure. New York: Abrams, 2019. Features original drawings and plans by Olmsted, Vaux, Mould, and others from the collections of the New York City Municipal Archives.

Cranz, Galen. The Politics of Park Design: A History of Urban Parks in America. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1982. The only comprehensive overview of the American parks movement and the evolution of the urban park from 1850 until the 1970s. The text provides a good context for understanding how the Park has changed over time.

Heckscher, Morrison H. Creating Central Park. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008. Published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to celebrate the sesquicentennial of the design of the Park, this is a concise but essential introduction to the design and construction of Central Park and an excellent source for key illustrations and photographs. Available for download online

Miller, Sara Cedar. Central Park, An American Masterpiece: A Comprehensive History of the Nation’s First Urban Park. New York: Abrams, 2002. This book by Sara Cedar Miller, Central Park Conservancy’s historian and photographer, is a fundamental history of the Park, heavily illustrated with contemporary photographs as well as numerous historic photographs and illustrations.

Olmsted, Frederick Law Jr. and Theodora Kimball, eds. Forty Years of Landscape Architecture. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1973. First published in 1928, this book is a collection of selected writings of Olmsted, Vaux, and others related to the design, construction, and management of the Park. Framed by commentary of the editors (Olmsted’s son and Kimball, the first librarian at the Harvard School of Landscape Architecture), it provides a history of the Park through some of the key primary source documents.

Rosenzweig, Roy and Elizabeth Blackmar. The Park and the People: A History of Central Park. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992. This thoroughly-researched interpretation of the social history of Central Park focuses on its designers, builders, and administrators as well as generations of Park users. The extensive footnotes are particularly useful for pointing researchers to primary source materials.

Schuyler, David. The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986. This seminal urban history text provides insight into the ideology and social history that informed the development of Central Park and the urban parks movement.

Biographies, Memoirs, and Papers

The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted. This series of ten volumes and a supplementary series, including several forthcoming volumes, provides a sampling of Olmsted’s writings. Three volumes are of particular use to researchers of Central Park::

- Beveridge, Charles E. and David Schuyler, eds. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: Vol III: Creating Central Park 1857-1861. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1983. This volume contains the full descriptive text and details of the Greensward plan — Olmsted and Vaux’s winning entry in the competition for the Park’s design — including the plan drawing keyed to their text, and accompanying illustrations. It also includes extensive correspondence with the Park Commissioners and others about the Park’s development.

- Schuyler, David and Jane Turner Censer, eds. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: Vol VI: The Years of Olmsted, Vaux, and Co. 1865 - 1874. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1992. This volume contains a good deal of writing on Central Park, including reflections upon its design while designing Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

- Beveridge, Charles E., Carolyn F. Hoffman, and Kenneth Hawkins, eds. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: Vol VII: Parks, Politics, and Patronage 1874 - 1882. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2007. Although this volume is largely focused on Olmsted’s other projects, it does include writing about Central Park, covering the period prior to his dismissal from the Parks Department and later reflections on his work in Central Park, highlighting the political difficulties within the Parks Department.

Beveridge, Charles E., Lauren Meier, and Irene Mills, Eds. Frederick Law Olmsted: Plans and Views of Public Parks. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2015. A visual survey of Olmsted’s plans for public parks. The first 50 pages detail the Greensward plan and Central Park.

Caro, Robert. The Power Broker. New York: Vintage Books, 1974. This substantial biography of Robert Moses, NYC Parks Commissioner from 1934 – 1960, is a key resource for insight into his influence in Central Park.

Hecksher, August. Alive in the City: A Memoir of an Ex-Commissioner. New York: Scribner’s, 1974. August Hecksher was the Commissioner for the Department of Recreation and Cultural Affairs from 1967 – 1973, a tumultuous time in the history of Central Park. This memoir is one of the few resources on this period of the Park’s history.

Kowsky, Francis R. Country, Park & City: The Architecture & Life of Calvert Vaux. Oxford University Press, 2003. This illustrated biography of Vaux provides enormous insight into his career and work in Central Park.

Parsons, Mabel, ed. Memories of Samuel Parsons, Landscape Architect of the Department of Public Parks, New York. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1926. This volume contains the compiled recollections of Samuel Parsons, who began his career in Central Park in 1881 as Superintendent of Planting under Vaux and became Landscape Architect for the Department, remaining until 1911. It includes accounts of struggles to preserve the original intent of the Park and to guard against various proposed encroachments

Olmsted Biographies

Martin, Justin. Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2011.

Roper, Laura. FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Rybczynski, Witold. A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the 19th Century. New York: Touchstone, 1999.

Guidebooks & Descriptions

Cook, Clarence. A Description of the New York Central Park. New York: F.J. Huntington, 1869. (Reprint 1979, B. Blom.) One of the key primary sources on Central Park, this book provides a comprehensive description of Central Park in 1869, when it was close to completion, as well as a narrative of the developments leading up to the creation of the Park.

Forrester, Francis. Little Peachblossom, or Rambles in Central Park. New York: Nelson & Phillips, 1873. Subtitled “A Story in which many beautiful and interesting objects in Central Park, New York, are sketched with pen and ink, and the difference between a happy and a churlish disposition are incidentally illustrated,” this miniature novel follows four children on adventures in the Park led by their uncle and is an excellent primary source for the nineteenth century Park.

Perkins, F.B.. The Central Park: Photographed by W.H. Guild Jr., with Descriptions and a Historical Sketch by F.B. Perkins. New York: Carleton, 1864. This was the first guide to Central Park, published while the Park was still under construction. It includes detailed descriptions of the Park’s landscapes and insights into its significance to the City.

Reed, Henry Hope and Sophia Duckworth. Central Park: A History and a Guide. New York: C. N. Potter, 1967 (revised 1972). Reed, a critic and historian who was appointed curator of Central Park in 1967, wrote this history and guide with Sophia Duckworth, to help advocate for the preservation of the Park during a period of decline. It includes a walking tour with some descriptions of the Park at this time.

Contemporary Guides

Barnard, Edward Sibley and Neil Calvanese. Central Park: Trees and Landscapes, A Guide to New York City’s Masterpiece. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Barnes and Noble Complete Illustrated Map and Guidebook to Central Park. New York: Silver Lining Books, 2003.

Miller, Sara Cedar. Seeing Central Park: The Official Guide to the World’s Greatest Urban Park. New York: Abrams, 2009.

Additional History

Alex, William. Calvert Vaux: Architect & Planner. New York: Ink, 1994. This richly-illustrated monograph on the buildings and landscapes designed by Calvert Vaux includes a large section on his work in Central Park.

Ballon, Hilary and Kenneth T. Jackson, eds. Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007. This exhibition catalogue provides a comprehensive overview of Moses’ building projects and insight into his legacy. It includes a brief section on the projects executed in Central Park during his tenure as Parks Commissioner.

Barlow, Elizabeth. Frederick Law Olmsted’s New York. New York: Praeger, 1972. Published on the occasion of an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the book reflects the resurgence of interest in Olmsted during the 1970s and provides an overview of Olmsted’s work in New York, focusing on Central and Prospect Parks. The author went on to become the first Central Park Administrator and founding president of Central Park Conservancy.

Barlow, Elizabeth, Vernon Gray, Roger Pasquier, and Lewis Sharp. The Central Park Book. New York: The Central Park Task Force, 1977. This workbook, intended to teach young adults Park history, was created by the Central Park Task Force, an early Park advocacy group and pre-cursor to Central Park Conservancy. It is most illuminating as a primary source document from this period when citizens began mobilizing to advocate for and restore the Park.

Fein, Albert. Frederick Law Olmsted and the American Environmental Tradition. New York: Georges Braziller, 1972. Published in 1972, this is one of the first books to rediscover Olmsted’s work and legacy of landscape design and city planning. It provides valuable historic context for Olmsted’s work and an overview of his career.

Graff, M.M. Central Park-Prospect Park: A New Perspective. New York: Greensward Foundation, 1985. This account of the history and design of Central and Prospect Parks by M. M. Graff—a writer, gardener, and parks advocate — provides a useful introduction to all those involved in creating the Park.

Kelly, Bruce, Gail Travis Guillet, and Mary Ellen W. Hern. The Art of the Olmsted Landscape. New York: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission & Arts Publisher, 1981. Simpson, Jeffery. The Art of the Olmsted Landscape: His Works in New York. New York: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission & Arts Publisher, 1981. This heavily illustrated, two-volume exhibition catalogue includes essays by various authors that discuss aspects of Olmsted’s work and career.

Levine, Edward J. Central Park (Postcard History Series). Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. A useful visual resource, this book includes postcards and photographs of the Park throughout its history.

Olmsted, Frederick Law. Civilizing American Cities. New York: Da Capo Press, 1997. While not focused on Central Park, this volume contains some of Olmsted’s seminal writing on parks and city planning.

Parsons, Samuel. The Art of Landscape Architecture. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915. Rpt. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009. In this book, Parsons elucidates his theories and practice of landscape architecture, often citing Central Park as an illustration of various design concepts. The introduction by scholar (and Vaux biographer) Francis Koswky establishes Parsons’ relationship and contributions to the preservation of Central Park.

Parsons, Samuel Jr. Landscape Gardening. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1891. Focused on landscape gardening theories and techniques, this book includes a chapter on city parks that discusses landscape effects and planting in Central Park.

Reiss, Marcia. Central Park Then and Now, San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2009. A rich visual resource, this book juxtaposes historic and contemporary photos of park landscapes and activities.

Spiegler, Jennifer and Paul M. Gaykowski. The Bridges of Central Park. Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. This survey of the more than fifty arches and bridges that Olmsted and Vaux designed as part of the circulation system of the Park is heavily illustrated with historic and contemporary photographs and provides insight into some of the Park’s most well-known built features.

Wurman, Richard Saul, Alan Levy, Joel Katz. The Nature of Recreation. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1972. Published as part of the sesquicentennial celebration of Frederick Law Olmsted’s birth that included the exhibit of the Whitney Museum of Art, this tribute consists of contemporary interpretations of Olmsted’s ideas about urban recreation.

Zega, Andre and Bernd H. Dams. Central Park: An Architectural View. New York: Rizzoli, 2013. This book focuses on the Park’s bridges, buildings, monuments, and sculptures, and includes contemporary illustrations and photographs, as well as history.

Natural History

Burton, Dennis. Nature Walks of Central Park. New York: Henry Holt, 1997 (revised 2014). This guide suggests walks in different areas of the Park and provides information on the trees and shrubs commonly found there. Descriptions are interspersed with information about the Park’s design and historic significance.

Graff, M.M. Tree Trails in Central Park. New York: Greensward Foundation, 1970. Provides information about trees in Central Park and a series of walking tours.

Hanley, Thomas and M.M. Graff. Rock Trails in Central Park. New York: Greensward Foundation, 1976. Provides a geologic history of the Park and a series of walking tours focused on rocks.

Peet, Louis Harman. Trees and Shrubs of Central Park. New York: Manhattan Press, 1903. This book is an important historic record of the vegetation in the Park in the early twentieth century.

Vornberger, Cal. Birds of Central Park. New York: Abrams, 2005. This book features impressive photographs by Vornberger of a great variety of birds in Central Park, accompanied by his commentary on the birds and the Park.

Winn, Marie. Central Park in the Dark: Mysteries of Urban Wildlife. New York: Picador, 2008. This book chronicles the littleknown lives of the nocturnal creatures in Central Park, providing a unique perspective on urban natural history.

Winn, Marie. Red-Tails in Love: A Wildlife Drama in Central Park. New York: Vintage Books, 1999. This book uses the story of Pale Male, the red-tail hawk that nested atop a Fifth Avenue apartment, to delve into the rich natural history of Central Park and reveal the surprising interactions between wildlife and the city.

Field Guides

Barnard, Edward. S. New York City Trees. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. Produced in consultation with the Department of Parks and Recreation, this book contains a wealth of information about the more than 125 tree species growing in New York City, including color photographs, detailed maps, and drawings. This is a useful guide for identifying trees in Central Park, and the book includes two recommended tree walks.

Day, Leslie. Field Guide to the Natural World of New York City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2007. This guide provides a comprehensive natural history of New York, different chapters on the wildlife, plants, and geology found in the city, and features on New York City parks, including Central Park.

Fowle, Marcia T. & Paul Kerlinger. The New York City Audubon Society Guide to Finding Birds in the Metropolitan Area. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001. The Audubon Society’s detailed guide to birding in New York includes a chapter on Central Park, considered by the Society to be one of the best birding sites in the country.

Peterson, Russell Francis. The Pine Tree Book (2nd ed.). New York: Central Park Conservancy, 2004. This field guide to pine trees is based on the Arthur Ross Pinetum in Central Park, a landscape established in the 1970s that includes 17 different species of pine tree.

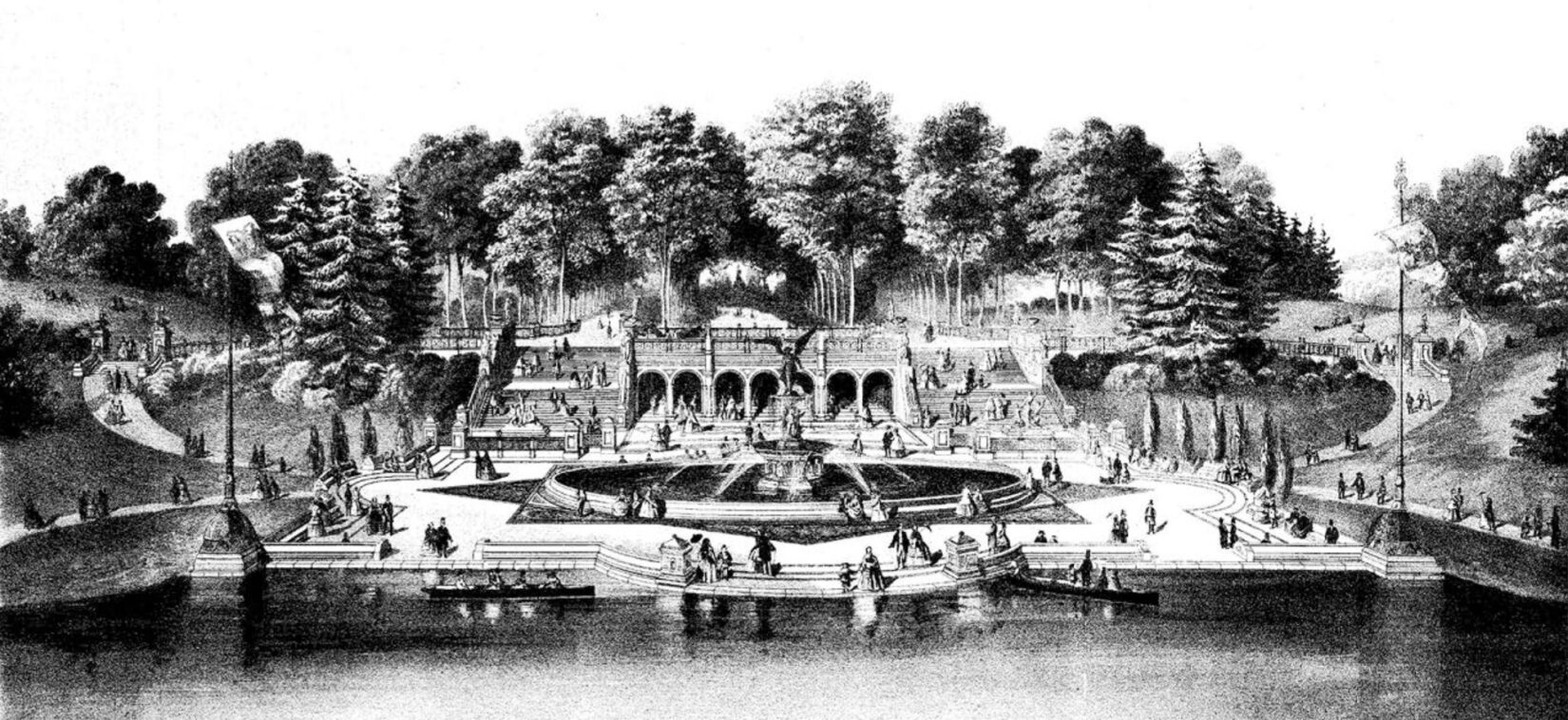

Illustration of Bethesda Terrace, published in the Sixth Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, 1863

Historic Records & Unpublished Papers

Historic records and personal unpublished papers offer researchers great insight into the Park, particularly its early history.

Typically the most useful of these documents are the historic annual reports and minutes published by the Board of Commissioners of Central Park while the Park was being constructed. Often highly detailed records, they provide information about materials and construction processes, visitors and use, finances, and more. They also include drawings and photographs.

Annual Reports

From 1857 until 1873 the administrators of Central Park issued bound reports detailing the development of the Park. Known initially as the Board of Commissioners of Central Park, this group was created in 1856 to build and maintain Central Park. They soon became responsible for the emerging park system of the City of New York, as well as other aspects of the city’s growth and infrastructure, and were reorganized in 1870 as the Department of Public Parks (DPP) in the City of New York.

The onset of a nationwide economic depression in the fall of 1873 essentially halted construction of the Park and led to reorganization of the Parks Department. From 1873 - 1897, no annual reports were produced, although minutes of the commissioners’ meetings continued to be kept.

In 1898, the outer boroughs were consolidated to become the City of New York, and the Department of Public Parks of the City of New York resumed the publication of Annual Reports and continued producing them until 1916. Subsequently, each borough formed its own Department of Parks responsible for annual reports. Reports for the borough of Manhattan were only published from 1927 to 1932.

The historic annual reports and minutes are available via the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation website.

Physical copies of the reports are also available at some city libraries, including the New York Public Library and the City Hall Library, the reference library that is part of New York City’s Department of Records.

From 1934 to 1964, the Parks Department published reports approximately every two years. Entitled “Year of Progress,” they document the efforts of the Robert Moses-led administration to build new parks, playgrounds, and other recreational facilities. While they are not very detailed, they do include some information about Central Park and are generally valuable for considering this period in the Park’s history. These are available at the City Hall Library.

The final report from 1964 is available on the Parks Department’s website. Created during the administration of Parks Commissioner Newbold Morris, it documents the work of the Parks Department from 1934 – 1964.

In 1966, under Mayor John Lindsay, the Parks Department was restructured and absorbed the Office of Cultural Affairs. The newly-formed Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Affairs oversaw botanical gardens, libraries, and museums, as well as parks. 1967 and 1972 are the only annual reports published in this period. These are available in the City Hall Library.

Since Central Park Conservancy was formed in 1980, it has published annual reports detailing the work in the Park. These are available on the Conservancy’s website.

Department of Parks Files & Press Releases

Department of Parks Files

This collection of the NYC Municipal Archives includes correspondence, news clippings, printed materials, maps, contracts, reports, and other materials that concern every aspect of parks administration from 1934 – 1966. Much of the material is available for viewing on microfilm. The original files are stored offsite and available to researchers through special arrangement.

Department of Parks Press Releases

Press releases issued by the Department of Parks between 1934 and 1970 have been digitized and are available online.

These include information on new construction, restoration projects, and events and programs in Central Park during this period.

Papers

Olmsted Papers

The papers of Frederick Law Olmsted and his firm have been edited and published in the multi-volume series published by Johns Hopkins University Press. The majority of these papers are found at the Library of Congress. Refer to the following guide and finding aid.

Additional unpublished documents, including drawings, plans, and correspondence, are held at the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site in Brookline, Massachusetts, which was the headquarters of his firm starting in 1881 and is now a National Historic Site managed by the National Parks Service.

The Olmsted Research Guide Online (ORGO), a collaborative venture between the National Association of Olmsted Parks and National Park Service, offers a single database for the records from the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site and Library of Congress.

Vaux Papers

Most of Vaux’s personal papers (and the papers of Downing and Vaux, 1850 – 1852) have not been located. The New York Public Library has a limited collection of his correspondence along with documents, drawings, maps, plans, reports, news clippings, and other printed matter. The collection, excluding the portfolio of drawings, is available to researchers on microfilm (one roll).

Moses Papers

The manuscript records of the NYC Municipal Archives include the records of the Office of Parks Commissioner, 1940 – 1975. Within this collection is the correspondence of Robert Moses (1934 – 1959). The collection in its entirety is available for viewing on microfilm. The Robert Moses Archive is part of the Manuscripts and Archives collection of the New York Public Library. This collection consists of correspondence, speeches, reports, photographs, clippings and other printed and graphic materials documenting the career of Robert Moses. This includes Parks Department files.

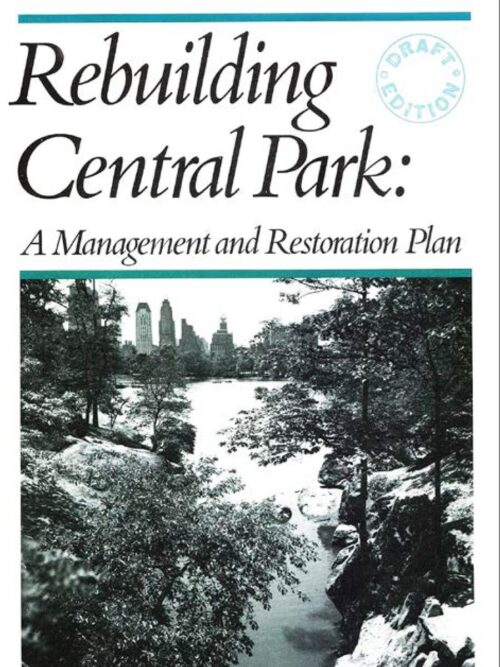

Cover of Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan, New York, Central Park Conservancy and New York City Department of Parks & Recreation; First Edition edition, 1985

Park Plans & Studies

The materials described in this section consist of park plans and studies, most of them created or commissioned by the Parks Department, and later, by Central Park Conservancy.

They include studies of the entire park, such as Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan, which examined many aspects of the Park, including use, vegetation, circulation, and architecture. Other studies focus on specific areas of the Park, such as the woodlands or playgrounds.

While some of the material in this section has been published in full or in part, the majority has not. Some of it is included in the collections of various research libraries. Materials not available in other libraries may be made available by Central Park Conservancy to qualified researchers by special request. For more information, please see Appendix 3: Research Policy

Parkwide Plans, Studies, and Inventories

Bresnan, Adrianne & Joseph for New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYCDPR). Master Plan: A Proposal for Program of Rehabilitation for Central Park: Design and Construction 1974 – 1984, 1973. This plan prepared by Parks Department staff represents an effort to identify and prioritize capital project needs; the authors proposed a phased program for addressing the Park’s severe deterioration.

Central Park Conservancy and NYCDPR. Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan. New York: Central Park Conservancy, 1985. This comprehensive plan for the restoration and management of the Central Park has served as the framework for the work of Central Park Conservancy. The plan was the result of a three-year planning study, led by Central Park Administrator Elizabeth Barlow and involving a large team of landscape architects, consultants, and planners. The plan integrated the findings of ten individual planning studies that are listed below. It was also produced as a book published by MIT Press, which is widely available at research libraries.

- Central Park Conservancy & NYCDPR. Central Park Tree Inventory: Parkwide Summary Data and Parkwide Raw Data, 1982. A catalogue of every tree in the Park in 1982.

- Central Park Conservancy. Soil Survey and Management Report, 1981.

- The Ehrenkrantz Group. Central Park Structures Inventory, 1982. (2 Volumes) Basic descriptive information for nearly all existing and vanished structures in the Park.

- Kornblum, William and Terry Williams, City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center. New Yorkers and Central Park, 1983. This remains the most extensive user surveys that CUNY professor of Sociology William Kornblum has conducted for the Conservancy over the years. The central conclusion — that a majority of visitors to Central Park came to engage in passive recreation, while smaller but highly significant numbers came to engage in active recreation and events — played a pivotal role in justifying a restoration and management approach that was to be guided by the historic intent of the Park as a pastoral retreat, while accommodating as much as possible of the ever-increasing and changing demands of contemporary use.

- Lockwood, Kessler, and Bartlett Consulting Engineers for Central Park Conservancy. Central Park Hydrologic and Hydraulic Study, 1983. Analysis for the planning for effective waterbody management.

- Vitullo-Martin Thomas & Julia, Metroconomy, Inc. Making Central Park Safer: A Plan for Improving Protective Services in Central Park, 1983.

- Winslow, Philip. Central Park Circulation Study. 1983. Examination of circulation systems and patterns including pedestrian, vehicle, and equestrian. Includes parkwide recommendations for reorganizing systems and redesigning their components to accommodate circulation requirements while preserving and enhancing the character of the landscape.

- Cramer, Marianne, Judith Heintz, and Bruce Kelly, Central Park Conservancy. Vegetation in Central Park, 1984. A detailed history of vegetation in the Park with recommended approaches relevant to restoration and management of the landscapes.

- Central Park Conservancy. Central Park Management Study, 1984. Extensive analysis of all aspects of the existing management of the park — including staffing and organization, space and equipment, use and policy — and recommendations for improved management.

- Hecklau, John. Central Park Wildlife Inventory, 1982. Examination of the range of species in the Park and their habitat requirements.

Central Park Conservancy. Report on the Public Use of Central Park, April 2011. This report is based on the most comprehensive study of Park use in its history, a follow-up to William Kornblum’s study in 1983. It incorporates survey and count data collected between July 2008 and May 2009, during all four seasons, and at each of the Park’s 61 entrances. One of its main conclusions was that there was a dramatic increase in use since the 1980s, with an estimated 37 – 38 million visits per year, by 8 – 9 million different people. Available online.

Demcker, Robert. Central Park Plant List and Map Index of 1873. Published by the Frederick Law Olmsted Association and The Central Park Community Fund, 1979. This inventory of the trees and shrubs in the Park, ordered by Olmsted in 1873 and was keyed to a map of the Park, provides an important record of what was originally planted. It was indexed geographically and published in 1979.

Kornblum, William, Julia Navarez, and Rolf Meyersohn. Report to the Central Park Conservancy: Market Research and Focus Groups, 1996. This user survey and focus groups were conducted to provide information about park users and perceptions of the Park, with particular emphasis on questions of interest to the Lila Wallace Readers Digest initiative focused on programming and the visitor centers.

Kornblum, William, CUNY Graduate Center. Central Park and Its Public: Changing Demands, New Challenges, 2000. The Conservancy commissioned a series of twelve focus groups to gather information about park users and their perceptions as part of its strategic planning initiative at that time.

Merkel, Hermann W. for the Commissioner of Parks, Borough of Manhattan. Report of Survey of Central Park with Recommendations, 1927. This report on the condition of Central Park was commissioned by the Department of Parks and conducted by Hermann W. Merkel, superintendent of the Westchester County park system. Known as “The Merkel Report,” it documented a general decline in the condition of the Park and made a series of important suggestions for its future maintenance. Merkel was the first to suggest the installation of playgrounds near park entrances and benches set in concrete footings along pedestrian paths.

Olmsted, Frederick Law and Calvert Vaux. Description for a Plan for the Improvement of the Central Park “GREENSWARD,” 1858. Olmsted and Vaux’s winning competition entry for the design of the Park included a plan view of their proposed design accompanied by a written description of the landscapes and features, a series of photographs documenting the existing conditions, and watercolor renderings illustrating the intended transformation.

Portions of the “Greensward plan,” as it is typically known, especially the original plan drawing, have been reproduced in numerous publications, many of which are included in the “Bibliographic Material” section. The most comprehensive publication of the plan is found in The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. III, which contains the full text and plan drawing as well as the illustrative studies that accompanied them. The Greensward plan and accompanying illustrations are in the collection of the Municipal Archives.

Pirnie, Malcolm, Department of Environmental Protection. Water Quality Management for Central Park: Draft, 2000.

Governance and Management Reports

Davis, Gordon, NYC Parks Commissioner. Report and Determination in the Matter of Christo, The Gates, 1980. In this 1979 review of the artist Christo’s proposal to install “The Gates” in Central Park, Commissioner Davis identified the criteria for evaluating proposals for large events against their potential impact on the Park and its users, and explained the City’s reasons for rejecting the proposal at that time.

Lindsay, Nancy, compiler. Highlights of the Panel Discussions and Responses: Speak out for the Future of Central Park, 1978. Transcript of a public symposium hosted by Manhattan Borough President Andrew J. Stein to address Central Park’s alarming deterioration and generate discussion about ways to reverse its decline; panelists included Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and the discussion included a proposal to make Central Park part of the National Park System.

NYC Department of Parks and Recreation. Report and Findings: Central Park Easter Egg Hunt, April 18, 1981. An internal report conducted under NYC Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis addressed the subject of management of Central Park events, in the context of an analysis of problems arising from inadequate planning and coordination for the Park Department’s 1981 Easter Egg Hunt.

New York Interface Development Project for The Central Park Community Fund. An Evaluation of Alternative Governance Proposals for Central Park, 1978. Drawing heavily on the 1976 Savas study and the premise that the most important requirement for improved management was to establish the Park as a unified entity for management purposes, this report analyzed the range of governance mechanisms that had been proposed for the Park, and concluded by recommending the establishment of a park administrator and a board of guardians serving in a fundraising and advisory capacity. (Elizabeth Barlow was appointed Park Administrator in 1979, and the Conservancy was founded in 1980).

Savas, E. S. for Columbia University. A Study of Central Park, 1976. This study was commissioned from Columbia professor of Public Administration E.S. Savas by concerned citizens Richard Gilder and George Soros, who founded the Central Park Community Fund. Based upon analysis of the Parks Department’s management of Central Park in the early 1970s, the study concluded that a fundamental lack of planning, supervision, and accountability — more than the declining number of personnel — was to blame for the inadequate maintenance of Central Park. It recommended, for the first time, appointment of a Chief Executive Officer for Central Park and establishment of a Board of Guardians (eventually realized through creation of the position of Central Park Administrator and the Conservancy’s Board of Trustees).

Ukeles Associates for Central Park Conservancy. An Operations Plan for Central Park. 1992. Commissioned by the Central Park Administrator’s office and the Conservancy to assess the day-to-day maintenance and operation of the Park, this report confirmed the effectiveness of the zone gardeners who were assigned to specific (restored) areas of the Park; its recommendations were instrumental in advancing the Conservancy’s park-wide implementation of zone management.

Major Studies and Plans for Landscapes and Areas

Andropogon for Central Park Conservancy. Landscape Management and Restoration Program for the Woodlands of Central Park. Phase 1 Report: Consensus of the Interviews, Key Issues, and Initial Program Recommendations, 1989. The report provides guidelines for managing and restoring the woodlands in Central Park.

Central Park Conservancy. Plan for Play: A Framework for Rebuilding and Managing Central Park Playgrounds. New York: Central Park Conservancy, 2011. This comprehensive planning document includes a history of playgrounds in Central Park, an analysis of play in the Park, and design goals for rebuilding the Park’s playgrounds. Available online.

Central Park Conservancy. Reconstruction of the Great Lawn in Central Park: A Case Study of Public Private Partnership and Park Management, 1997. This case study documents the careful and inclusive planning process for the successful reconstruction and management of the Great Lawn—the largest and most complex capital project undertaken by the Conservancy to date, and one that provides useful insight into many aspects of what is required to restore and sustain the Park.

Central Park Conservancy. Turf Care Handbook, 2016. A guide to the successful turf care practices used by the Central Park Conservancy. Includes how the Conservancy’s turf care practices have changed over time, and the underlying principles guiding the Conservancy’s program. Available online.

Central Park Conservancy. Trash Management and Recycling Handbook, 2016. A tool for urban park managers who are developing trash management strategies. The handbook traces the evolution of trash removal and recycling in Central Park and details the Conservancy’s current comprehensive, sustainability-based system. Available online.

Hunter Research for Central Park Conservancy and NYCDPR. A Preliminary Historical and Archeological Assessment of Central Park to the North of the 97th Street Transverse Road. (vol. 1: Narrative and vol. 2: Historic Illustrations). 1990. This report provides an in-depth history of the northern end of Central Park, before the Park was built, and an analysis of the potential for archaeological resources in this area. Available on the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Hunter Research for Central Park Conservancy. Archaeological Testing and Monitoring: Fort Landscape Reconstruction Project, December 2013. This report describes the archaeological investigations conducted in conjunction with a project to reconstruct the Fort Landscape in the northern part of Central Park, which included the discovery of significant remnants of the area’s pre-Park history. Available on the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Hunter Research for Central Park Conservancy. Archival Research and Historic Resource Mapping, North End of Central Park Above 103rd Street, July 2014. As a follow up to the investigations in the Fort Landscape, archeologists studied the potential for additional archaeological resources in the northern part of Central Park. Available on the website of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Kelly, Bruce for Central Park Task Force and NYCDPR. The Ramble in Central Park: An Historic Landscape Report and Master Plan, 1980. This report on the Ramble, created in preparation for a restoration, includes history, analysis of existing condition and use, and various reports written by consultants on horticulture, birding, and visitor perceptions and experience.

Jaroslow, Abby. Restoration Study of Perimeter Wall and Gates at Central Park, New York City, 1984. Submitted as a project for Columbia University’s Historic Preservation Program, this report includes a comprehensive history of the perimeter wall and gates as well as recommendations for their preservation.

Illustrative Material

Drawings, Plans, and Maps

The building, and rebuilding, of Central Park is well-documented through drawings, maps, and plans dating from the original construction to more recent efforts of the Conservancy to restore the Park. There are three primary locations for drawings, plans, and maps, listed below. Additional historic maps can be found in the New York Public Library, Library of Congress, and the Olmsted Historic Site.

Municipal Archives, Department of Parks Collection

The Municipal Archives contains over 1,500 drawings created from 1850 - 1880 of all aspects of the design and construction of Central Park. (The collection also includes drawings for approximately 60 other New York City Parks.)

There is an item level catalogue of the drawings collection and they can be viewed on microfilm. There are also high-quality, 4”x5” color microfiche of approximately 600 of the drawings. Under special circumstances when the microfilm and microfiche do not provide sufficient information, researchers may request the opportunity to view the original drawings — many of which are extremely fragile. A selection of these drawings are available online now, as part of the digitization of the collection of the Municipal Archives.

NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, Capital Projects Division The Olmsted Center (Flushing, NY)

The design and construction office of the Parks Department retains plans and construction documents for capital projects in Central Park from the 1930s through much of the 1980s, during which period the design office of Central Park Conservancy assumed the function of design and bidding capital projects in the Park. The Olmsted Center is a professional office, not a research facility; qualified researchers who wish to access this material must call 718.760.6798 to make a special request of the Map Division, and are advised that not all research requests can be accommodated, particularly within a limited timeframe.

Central Park Conservancy, Planning, Design, and Construction Department.

The planning, design, and construction office of Central Park Conservancy has plans and construction documents for capital projects in Central Park from the 1980s — when the organization assumed the function of design and bidding capital projects in the Park — through the present. This department is a professional office, not a research facility; qualified researchers who wish to access this material must make a special request to the Conservancy. For more information, please see the Central Park Conservancy Research Policy section of this document.

Photographic Material

As the first urban park and a perennial destination for New Yorkers and visitors, Central Park has always been a popular photographic subject for both amateur and professional photographers. Photographs of Central Park are in the collections of some of the city’s major cultural institutions, many of whom have made their holdings available online, creating unprecedented access to the Park’s history.

Photographs of the Park in the nineteenth century are particularly valuable to understanding its history. The majority of these are stereographs, an early version of 3-D technology that was popular from the 1880s through the 1930s. Stereographs consist of two almost identical photographs pasted side-by-side on a board. When viewed through a stereoscope, a special device for viewing these photographs, they appear three-dimensional, augmenting the photograph’s illusion of reality. Stereographs often depicted exotic places or scenes, and were collected for both education and amusement. Stereographs created later were often hand-colored.

Each institution has different rules about access, rights, and reproductions. Please consult individual policies before publishing images or visiting in person.

Bettman Archive/Corbis Database:

The Bettman Archive is a collection of historic images now owned by Corbis. The collection includes many images of Central Park from the late 19th century and well into the 20th century. Many of the images were originally part of the collection of Underwood and Underwood, an important producer and distributor of stereoviews.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images:

The Bettmann Archive is a collection of historic images now owned by Getty. The collection includes many images of Central Park from the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century. Many of the images were originally part of the collection of Underwood and Underwood, an important producer and distributor of stereoviews.

Central Park Conservancy:

Central Park Conservancy has a collection of images that document work to restore the Park since the 1980s, including photographs of the Park’s condition before restoration, projects in the process of being constructed, completed restoration projects, workers in the Park, and events. There is also some documentation of restoration efforts conducted in the late 1970s before the Conservancy was formed. This collection has not been digitized and is only available to qualified researchers by appointment. For more information, please see Appendix 3: Research Policy.

Library of Congress (LOC) Prints and Photographs

LOC’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog includes a crosssection of the 15 million images from their collections, including photographs, prints, and drawings, posters, and architectural and engineering drawings, focusing on United States History. There are many images of Central Park in this catalog. Notable collections include:

- Gottscho-Schleisner Collection: The work of the photographer Samuel Herman Gottscho, most well-known for photographs of New York City interiors and buildings, photographed Central Park during the first half of the twentieth century. (His work is also in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.)

- Detroit Publishing Company Collection: The images of a prominent photographic publishing company active in the late nineteenth century through 1932. Collection includes many early twentieth-century photographs of Central Park.

- George Grantham Bain Collection: The photographs of one of America’s earliest news picture agencies, most active during the first quarter of the twentieth century, with an emphasis on life in New York City. Collection includes a number of early twentieth-century photographs of Central Park.

- Works Projects Administration (WPA) Poster Collection: Posters produced between 1936-1943 by various branches of the WPA. Includes posters for events and programs in Central Park.

Library of Congress American Memory Collection:

The American Memory Collection is another collection within the LOC’s holdings that contains a significant number of Central Park images. Created as a database of images from academic institutions, libraries, and museums, most of the Central Park images are found in the Study Collection from the Harvard School of Design. The images date from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the date given to all images is 1880, which is not always accurate.

The American Memory collection also includes a selection of early motion pictures including 3 short films that unfold in Central Park: “Skating on a lake” (1900), “Sleigh Scene” (1898), and “Mounted Police charge” (1896).

Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Herbert Mitchell Collection:

Herbert Mitchell was an avid collector of stereographs and postcards, who donated the bulk of his collection to the Met in 2007. The Met collection, which includes many rare images of Central Park, has been inventoried and some of it digitized, though the images are only visible as small thumbnails.

There are other photographs, paintings, and drawings of Central Park in the Met’s collection as well.

Municipal Archives Online Gallery:

The Municipal Archives is the repository for the historical records of the municipal government of the City of New York, including all the various city agencies. The online gallery was created in 2012 to provide access to a selection of these holdings. It comprises 900,000 items, including photographs, maps, motion-pictures, and audio recordings. Images from Central Park are primarily from the twentieth century. They are found in a number of collections, including the following:

- Department of Parks and Recreation: The photographs in this collection are primarily of Park projects implemented during the administration of Robert Moses, including the construction of Tavern on the Green, perimeter playgrounds, and the Zoo. This collection also includes important drawings, including many of the original drawings of the Park. (See the Drawings, Plans & Maps section of this document.)

- Borough Presidents Manhattan: During the first half of the twentieth century the Borough Presidents had jurisdiction over the construction and maintenance of street, sidewalks, and other urban infrastructure. This collection documents this work and includes numerous images of work done on the Central Park transverse roads.

- Municipal Archives Collection: There are a number of photographs from a variety of sources in this more general collection.

- Mayor Robert F. Wagner Collection: Photographs of the Park, its structures and facilities, during his tenure as Mayor (1954 - 1965).

- Mayor Ed Koch Collection: Selected images in this collection document the early efforts to restore the Park as well as important public programs during the period (1978 - 1989).

- WPA Federal Writers Project: This collection consists of the photographs used to illustrate publications sponsored by the Federal Writer’s Project and includes photographs of Central Park from 1935 - 1943.

Museum of the City of New York (MCNY) Collections Portal:

MCNY’s collection contains a variety of materials in various media regarding Central Park, the majority of these being photographs from the twentieth century. There are also many postcards of Central Park in the collection (categorized as ephemera), as well as paintings and drawings. The digitization of the collection began in 2010 and is ongoing. Notable photographers include:

- William Hale Kirk: Panoramic photographs of Central Park landscapes circa 1905. Some of these images were published in the Park Department Annual Reports.

- Byron Company Collection: This collection of photographs created by a prominent commercial studio active from 1890 - 1942 includes many images of Central Park taken around the turn of the century, including equestrian portraits and winter scenes.

- Samuel Gottscho: Most well-known for photographs of New York City interiors and buildings, Gottscho also photographed Central Park during the first half of the twentieth century. (His work is also in the collection of the Library of Congress).

- Wurts Brothers: Architectural photographers working in New York between 1894 and 1979, the Wurts brothers photographed Central Park in the 1902s - 1940s. (There are additional Wurts Brothers images in the collection of the New York Public Library, within the collection of photographic views of New York City, 1870s - 1970s).

New York Historical Society: Photographs of New York City and Beyond:

NYHS’s collection of prints, photographs, and architectural collections is comprised of over 500,000 prints and negatives. Much of the collection is comprised of portraiture and documentary photographs of New York City and its surroundings from 1839 to 1945. There are many images of Central Park, a selection of which can be viewed as part of the digital collection.

There are many images of Central Park that have not been digitized. Many are found within the collections listed below and described in the corresponding finding aids. Some of the finding aids are also searchable, allowing you to locate specific references to Central Park.

- Album Files: consists of personal photo albums

- Geographic File: images of New York from various sources organized by location or type of building or landscape; Central Park is within the “Parks and Gardens” category. Available online.

- Individual Collection Files: There are also images of Central Park within the collections of the following individuals: John Albok, Robert Braklow, Andreas Feiniger, Ruth Orkin, Robert M. Lester, Lewis F. White, and more.

New York Public Library Digital Gallery:

The NYPL’s digital gallery is an excellent resource for searching and viewing the library’s extensive collection of illuminated manuscripts, historical maps, vintage posters, rare prints and photographs, illustrated books, printed ephemera, and more. A key word search from the main search engine will yield many images of Central Park. Searching and browsing can also be accomplished from within the various collections that comprise the gallery. Notable collections include:

- Photographic Views of New York City, 1870s - 1970s: The majority of these are neighborhood scenes from the 1910s – 1940s. Most of the Central Park images are dated within this timeframe.

- Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views: One of the largest collections of stereographs, this includes many images of Central Park, mostly from the nineteenth century.

- Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection: This includes graphic materials, including postcards and illustrations from books, newspapers, and magazines.

- Victor Prevost photographs: This is not a collection, but a notable body of images of Central Park in the NYPL digital gallery. Taken by Victor Prevost, a photographer from France who was one of the first to work in New York, they depict the Park in 1862 while it was still under construction and are some of the earliest photographs of the Park. They were originally published in a portfolio by the Central Park commissioners, which is in the collection of the NYPL Rare Book Division. There are additional images from this series in the collection of the George Eastman House that have also been digitized and can be found here.

Parks Department Photo Archive

The Parks Photo Archive contains over 300,000 photographs created by the Parks Department from 1856 to 2001. The collection contains many images of Central Park, the majority of which are found in the following collections:

- Annual Reports Copy Negative Collection, 1865 - 1930: This consists of copy negatives of photographs and illustrations in the Annual Reports published by the Board of Commissioners of Central Park and later the Department of Public Parks. (See the Annual Reports section of this document.)

- Robert Moses Photo Collection, 1934 - 1966: The bulk of the collection consists of photographs taken after 1933, the majority of these from the period when Robert Moses was Parks Commissioner (1934 – 1960). The photographs of Central Park from this period include a strong emphasis on the Zoo and other new structures and facilities that were built during this time. Other collections of interest include:

- Sixties Collection, 1955 - 1969/Daniel Mc Partlin Collection, 1963 - 1986: Black and white acetate negatives created by staff photographers. These photographs overlap with the end of the Robert Moses Photo Collection, in date range, content, and the photographers involved.

- Slides and Positive Transparencies, 1950s - 1970s: Color slides created by staff photographers. Images document Parks features, events, landscape design, construction and monuments, and the majority date from late 1960s through mid-1970s.

A selection of these images can be viewed online.

The collection is housed at the Parks Department Capital Projects Division in Flushing Meadows Corona Park. For access, contact the Photo Archivist through their website.

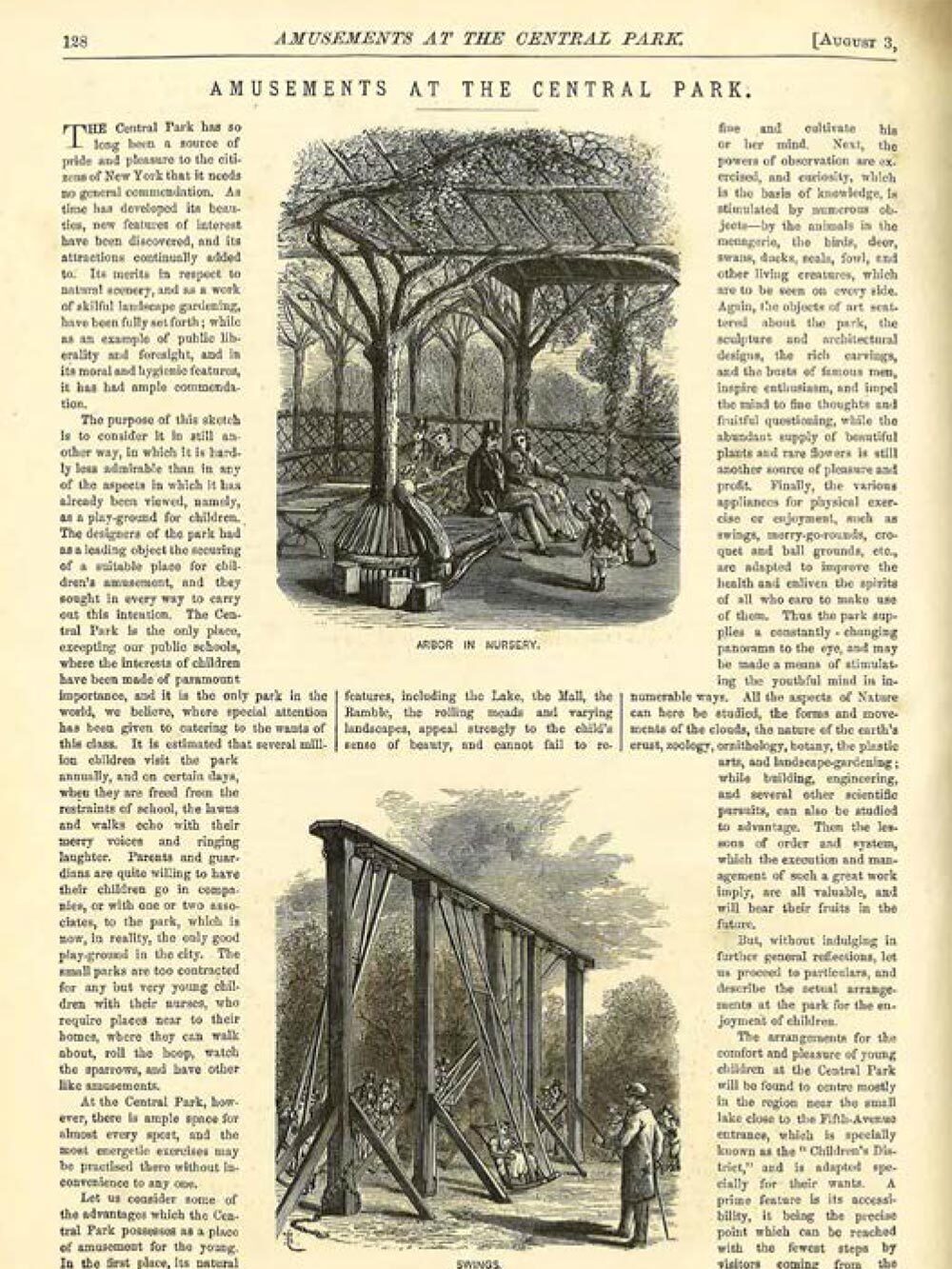

Page from Charles F. Wingate, “Amusements at the Central Park,” Appletons’ Journal 8, (August 3, 1873): 128-133.

Periodicals

Countless newspapers, journals, and magazines have covered Central Park over the last 150 years.

The publications listed here historically included extensive coverage of Central Park, particularly during the nineteenth century. In general, the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature, which was first published in 1892 and is available in any research library, can be relied upon to find articles on the Park in a given year in a wide range of periodical publications. Electronic indices and finding aids are also increasingly available; many enable users to conduct complex searches of one or more periodicals over time. The Microforms Section of the New York Public Library is a good resource for periodical research. They have microfilm of many of the major New York City newspapers.

New York City Newspapers

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

Numerous illustrated articles about the Park were published in Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in the nineteenth century. (The magazine was founded in 1852 and published until 1922.) Issues are available at NYPL on microfilm.

The Evening Post

The Evening Post has a special connection to Central Park by virtue of the fact that its editor was William Cullen Bryant (1794 – 1878), a key advocate for the Park’s creation who published his persuasive argument for the Park in an 1844 issue of the Post. This publication is available at NYPL on microfilm.

The New York Herald

Along with the Times and the Post, the Herald was one of the key New York City papers to cover the Park in its early years. (In 1924 it was acquired by the New York Tribune, becoming New York Herald Tribune.) It is also available through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

The New York Times

The ProQuest index of the historical New York Times (available on computer terminals at NYPL) goes back to 1851 and enables users to conduct complex, full-text keyword searches that may be limited by date, article type, and other considerations, and to immediately retrieve the full articles online.

Nineteenth-Century Periodicals

A number of nineteenth century periodicals that contained illustrated articles about Central Park have been digitized as part of the “Making of America” project, an effort to digitize materials focusing on the period from 1850 – 1877.

The following journals are accessible online:

- Harper’s Weekly

- Manufacturer and Builder

- Scribner’s Monthly

Garden and Forest: A Journal of Horticulture, Landscape Art, and Forestry.

Olmsted was a frequent contributor to this journal, which was published by his friend Charles Sprague Sargent, the founder of Arnold Arboretum in Boston. Available online.

Appendix 1: Timeline of Central Park History

This timeline includes milestones and significant events in the early history of the Park’s design, construction, and management.

It also includes a selection of important events in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

The creation of the country’s first large urban park was a response to unprecedented urban growth and the concerns about its effect on public health and vitality. It also recognized that a large open space in the city, providing urban dwellers with an experience of nature and recreation, could profoundly shape urban culture. The creation of Central Park was a major public works project, on par with the construction of the Croton Aqueduct system, and was a highly significant event in the history of New York City.

1800s

1851

Mayor Ambrose C. Kingsland recommends that the New York City Common Council consider creating a large park for Manhattan. The Council suggests Jones Wood, a 150-acre wooded area along the East River as a possible location. Problems with the Jones Wood site lead the city to consider a 775-acre rocky and swampy tract of land at the center of the island encompassing the existing reservoir and the planned location for an additional reservoir.

1853

The Central Park Act is passed by the state legislature. The boundaries of the Park—59th and 106th streets and Fifth and Eighth avenues—are confirmed. Three commissioners are appointed to assess the value of the properties of public and private owners.

1856

The three-year commission concludes its analysis, evaluating the cost to purchase the land at more than $5 million. The courts approve the study, and the Park becomes the property of New York City. The Common Council appoints the first commissioners to oversee the project, and they engage Egbert Viele, an engineer, to design the Park.

1857

The state legislature creates a new independent board of commissioners to replace the earlier city-appointed ones. They appoint Frederick Law Olmsted, most recently a writer and publisher, as the new superintendent of the Park, who will report to Viele and oversee clearing and draining the land. Calvert Vaux, a British-trained architect whose client is one of the new commissioners, convinces the board to reject Viele’s plan and, instead, hold a design competition. Vaux invites Olmsted, who he had met once before, to collaborate on a submission for the competition.

1858

In April, Olmsted and Vaux’s “Greensward,” a plan that simulates a sequence of rural landscapes, is chosen. Olmsted is appointed architect-in-chief of Central Park, and Vaux is appointed consulting architect. Jacob Wrey Mould is appointed assistant architect. By December, the Lake is filled with water and opens to the public for skating. Construction on the new reservoir begins.

1859

Three miles of the drive, the 65th Street Transverse Road, and the Ramble are completed. The earliest designs for Bethesda Terrace are made public. Work on the southern part of the Park is largely complete. The state legislature approves extension of the Park to 110th Street.

1860

Arches and paths are completed below 79th Street. The Pond is completed.

1861

Despite the Civil War, work continues, though in a diminished capacity. Olmsted takes a leave of absence to join the United States Sanitary Commission, formed to help treat sick and wounded Union soldiers. Landscapes are completed below 72nd Street with the exception of Bethesda Terrace. Annual visitation to Central Park is approximately 2.5 million. The new reservoir is filled with water.

1863

Olmsted and Vaux resign from Central Park, but are informally consulted on the work as it progresses. The land from 106th to 110th streets is added to the Park.

1864

Bethesda Terrace is largely completed. The Park’s plant nursery is moved from the Great Hill to the site of present Conservatory Garden.

1865

Olmsted and Vaux are reappointed landscape architects of Central Park and form a private partnership. They begin work on Prospect Park in Brooklyn, New York. Construction continues on Central Park, focusing on the northern section.

1870

In November, a new city charter transfers the control of New York City’s government from the state to a new city administration. The Board of Commissioners of Central Park is replaced by the new Department of Public Parks and overseen by a group of corrupt Tammany Hall politicians led by William “Boss” Tweed. Olmsted and Vaux are dismissed.

1871

The Tweed administration makes changes to the Park to emphasize it as a place of popular amusement. The Sheepfold and the Carousel are constructed, the Dairy becomes a popular eatery, and the Zoo is expanded. The administration is ousted after nineteen months, and Central Park is again under commissioners more sympathetic to the ideals of Olmsted and Vaux. They are reappointed as landscape architects and undo some of the work completed during this period.

1873

Bethesda Fountain is unveiled. Construction work is slowed because of lack of funds and economic panic, but most landscapes are completed.

1876

Construction of the Park’s perimeter wall is completed, largely concluding construction of the Park. The administration of the Park changes, and Olmsted loses much of his influence over the management and maintenance of the Park.

1878

The commissioners disband the office in charge of design and construction in Central Park and dismiss Olmsted’s position as landscape architect, though he is appointed an unpaid consultant.

1880

The Metropolitan Museum of Art opens in Central Park on a former lawn area.

1885

Vaux continues to work in Central Park as a landscape architect. Samuel Parsons, Jr., a landscape architect mentored by Vaux, becomes superintendent of Central Park.

1892

State legislature approves the straightening of the West Drive for a trotter race track. Citizen outrage is strong, and the plan is repealed six weeks later. This is the first instance of public protest over an alteration to the Park.

1895

Vaux dies in Brooklyn, New York. Samuel Parsons, Jr. becomes Landscape Architect for the Department of Public Parks.

1898

As part of the consolidation of New York, the Department of Public Parks is reorganized and named the Department of Parks of the City of New York. The department is overseen by three commissioners, responsible for parks in each borough. Central Park is managed by a commissioner of parks in charge of Manhattan and Staten Island.

1900s

During the early twentieth century, increasing use and crowds contribute to the deterioration of park landscapes and facilities. In addition, there are numerous proposals for additions to the Park, most of which are successfully fought by citizens seeking to preserve the Park’s landscapes and original purpose as a rural retreat. Beginning in 1934, numerous new structures and facilities are added to the Park by the administration of Robert Moses.

1903

Olmsted dies in Massachusetts.

1911

Samuel Parsons Jr. is dismissed after a disagreement with the Parks Commissioner Charles Stover, a former settlement worker focused on creating playgrounds and park programming.

1927

Central Park’s first playground, Heckscher Playground, opens in the southern part of the Park. A report documenting the Park’s deteriorating condition by consulting landscape architect Herman Merkel is completed. Merkel’s suggestions include the creation of playgrounds along the perimeter of the Park; new paths to better accommodate large numbers of visitors; and benches with durable concrete footings.

1930

The draining of the original reservoir begins. The design for a large oval lawn in its place is adopted.

1934

Robert Moses becomes Parks Commissioner overseeing a single unified department. He embarks on a massive modernization of the city parks system with funds from the New Deal that includes significant work in Central Park. Many of the new projects follow the recommendations of Herman Merkel. One of the first is the reconstruction of the zoo.

1935-37

Eighteen playgrounds are constructed along the perimeter of the Park. The greenhouse of Conservatory Garden is razed and is replaced with a new six-acre garden. The Great Lawn is completed.

1950s

Numerous original structures designed by Vaux are destroyed, including the Dairy loggia, Mineral Springs pavilion, and the Kinderberg. New buildings are constructed, including Loeb Boat House, Kerbs Boat House, Chess and Checker House, and the Carousel building. Views and landscapes are altered as backstops and diamonds are added to North Meadow, the Great Lawn and Heckscher Ball Field.

1956

Protests over the expansion of Tavern of the Green restaurant, including the construction of a parking lot in an area of landscape, results in what the press call the Battle of Central Park. Ultimately the landscape was destroyed by the construction, but a playground is built instead of the parking lot.

The Park begins to fall into a decline, as many of the projects implemented by Moses’ administration were not adequately maintained, and the overall landscape was not well-managed. The Park’s condition worsens as a result of numerous large events in the mid-1960s and a fiscal crisis in the mid-1970s; by the end of the decade, it is in ruins. This crisis prompts both citizens and the city to begin planning a solution, which ultimately leads to the formation of Central Park Conservancy.

1960

Robert Moses retires as Parks Commissioner.

1962

The Delacorte Theaters opens.

1965

Central Park is declared a National Historic Landmark by the U. S. Department of the Interior.

1966

Mayor Lindsay appoints Thomas Hoving as Parks Commissioner. The Park is increasingly used for large scale events, including concerts, festivals, and protests. This is the first time the park drives are closed to vehicle traffic during certain hours.

1974

Central Park is designated New York City’s first Scenic Landmark. The Central Park Community Fund is founded by a group of private citizens to address the Park’s condition.

1975

At the height of the City’s fiscal crisis, budget cuts result in massive layoffs within the Parks Department. The Central Park Task Force is formed, a privately-funded program for high school students who carry out small-scale restoration projects in the Park. Elizabeth Barlow—an urban planner and writer on New York’s natural history and Olmsted legacy—is appointed Executive Director.

1976

Columbia Professor E.S. Savas’ A Study of Central Park, commissioned by the Central Park Community Fund, is made public. The study concludes that a fundamental lack of planning, supervision, and accountability—more than the declining number of personnel—is to blame for the inadequate maintenance of Central Park. The study recommends, for the first time, appointment of a Chief Executive Officer for Central Park and establishment of a Board of Guardians

1979

Mayor Koch and Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis appoint Barlow as the first Central Park Administrator with the authority to consolidate all planning, management, and interagency coordination pertinent to Central Park under one office.

1980

The Central Park Task Force and the Central Park Community Fund join to form Central Park Conservancy the “Board of Guardians” suggested in the Savas study. Its early initiatives include: recruitment of interns for horticulture and preservation projects; restoration planning; the use of the Dairy as a visitor center; and fundraising for hiring staff and equipment.

1985

The Conservancy completes Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan, which synthesizes parkwide studies conducted from 1982-84 into a comprehensive blueprint to guide the restoration and management of the Park.

1986-91

The Conservancy’s first capital campaign raises $50 million over a five-year period and funds major restoration projects including Bethesda Terrace, Grand Army Plaza, the Shakespeare Garden, the Mall, and Cedar Hill and annual maintenance.

1989-90

Citizens Task Force on the Use and Security of Central Park, chaired by Ira Millstein, studies the security challenges and perceptions of the north end of the Park.

1991

In the face of City budget cuts affecting the Parks Department’s spending in Central Park, the Conservancy makes a commitment to raise funds toward the shortfall, and moves into areas of general maintenance that had previously been provided by the City.

1993

The Conservancy opens the Charles A. Dana Discovery Center on the newly restored Harlem Meer in the northern part of Central Park. It is the first building created as a visitor center in the Park.

1996

The Conservancy fully implements the zone management system. The Park is divided into 10 sections and 49 zones, each with a gardener assigned to it, introducing accountability for daily maintenance of the individual landscapes.

1998

With the Park’s major landscapes restored, Central Park Conservancy and the Parks Department sign an agreement for the management of the Park. The agreement formalizes the Conservancy’s role as the official keeper of the Park, charged with specific maintenance and fundraising responsibilities.

2000s

2005

The Gates, a temporary site specific art installation by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, is installed in Central Park.

2010-11

The Conservancy launches the Central Play initiative to fund projects in playgrounds and publishes Plan for Play, a planning document intended to guide this effort.

2011

A user survey organized by the Conservancy is the most systematic and comprehensive effort to analyze Park use. It reveals that the Park receives 37-38 million visits annually.

2012

The Conservancy secures a $100 million gift towards restoration and management of the Park. Roughly half of the funds are directed toward a 10-year capital program for the Park.

2013

The Conservancy signs a new expanded management agreement with the City, and it launches the Central Park Conservancy Institute for Urban Parks as the educational arm of the organization.

2014

The Conservancy creates a Five Borough Crew to offer on-site support and training for Parks Department staff in parks throughout the boroughs of New York City.

2016

The Conservancy launches Forever Green: Ensuring the Future of Central Park, a ten-year campaign that builds upon the organization’s decades-long investment in essential rebuilding and infrastructure. The campaign aims to raise $300 million to enable vital long-term planning and restoration throughout the entire Park including the woodlands, buildings, and playgrounds.

2017

The restoration of the Ravine is completed, as part of the Conservancy’s Forever Green campaign to renew and sustain woodland landscapes in the Park. Restoration work included the removal of accumulated sediments from the Loch, a complete reconstruction of paths and infrastructure, improvements to the planting and irrigation systems, and the restoration and reconstruction of rustic bridges and stone steps.

2019

The restoration of the Belvedere is completed. This project addressed the overall condition of the Belvedere structures and terraces, modernized systems that support its preservation and use, and restored lost aspects of the historic design.

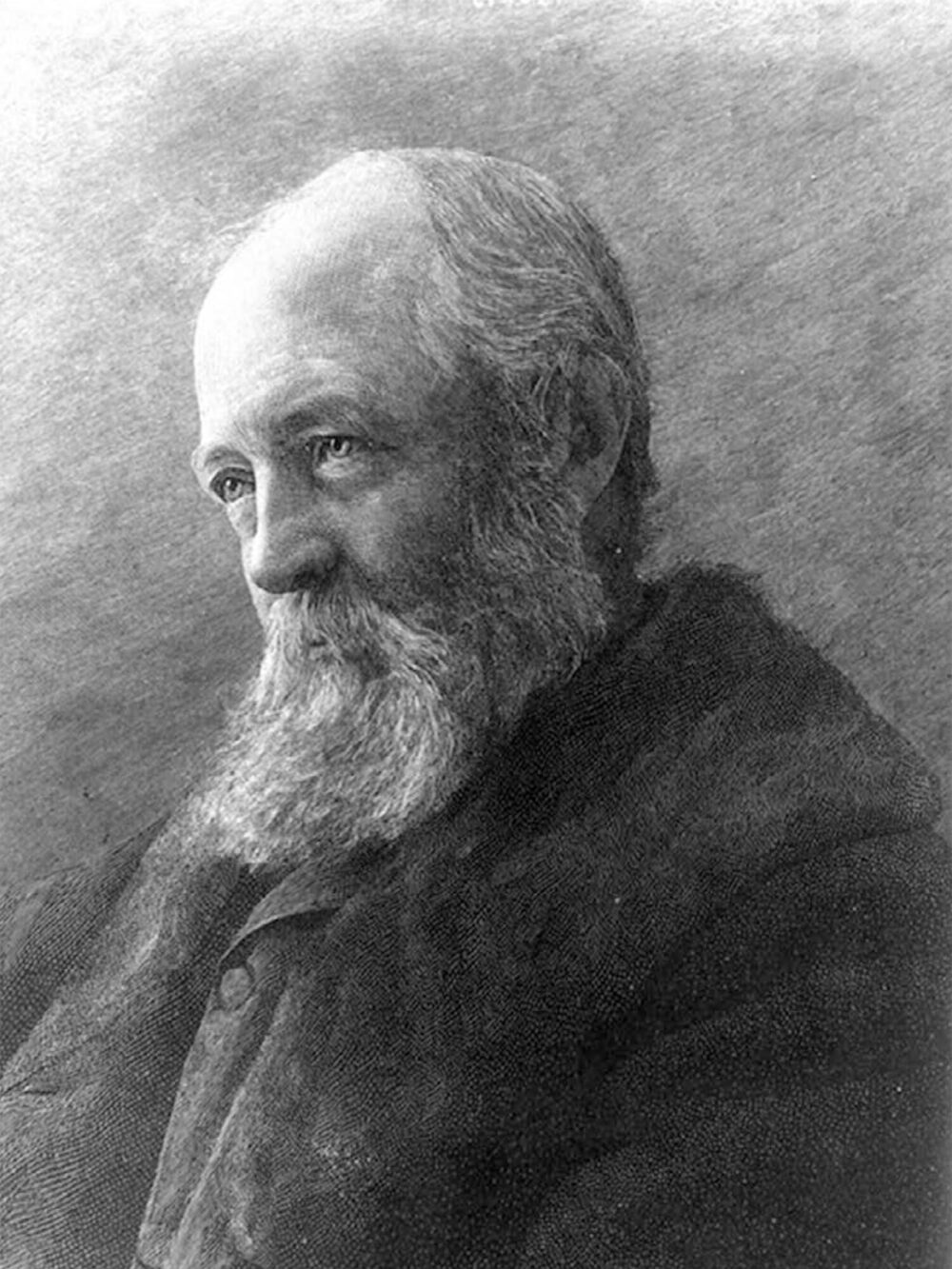

Portrait of Frederick Law Olmsted, 1893, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Appendix 2: Biographies

Important figures in the early history of Central Park

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822 – 1903)

Co-designer of Central Park and “the father of landscape architecture in America.” Olmsted began his career in 1857 as the superintendent of Central Park, overseeing clearing of the land under engineer Egbert Viele. Prior to working in Central Park, Olmsted was an author, journalist, and gentleman farmer. After designing Central Park with Calvert Vaux, the two formed a partnership. With Vaux, and in his own firm, he went on to design many parks, college campuses, and other landscapes throughout the United States including the grounds for the 1893 Columbia Exposition. He spent more time working hands-on in Central Park than any other landscape and wrote prolifically about the Park.

Calvert Vaux (1824 – 1895)

Architect, landscape architect, and co-designer of Central Park. Vaux came to America from his native Britain to work as an architect for Andrew Jackson Downing. Following the death of Downing, Vaux continued to design country houses. In 1856, he moved to New York to pursue other opportunities. Aware of the plans for Central Park, and disappointed with the accepted design by Egbert Viele, Vaux urged the Board of Commissioners to sponsor a design competition. He approached Olmsted to partner with him, and “Greensward,” their winning submission, became the basis for the design of Central Park. Vaux was involved in the design of the Park’s landscapes and also designed many of the structures in the Park, including the bridges and arches, Belvedere Castle, the Dairy, and Bethesda Terrace. He went on to design additional parks and landscapes with Olmsted. He was a founding member of the American Institute of Architects and practiced architecture throughout the country.

Andrew Jackson Downing (1815 – 1852)

Landscape gardener, editor of the magazine The Horticulturist, and the author of numerous books about the design of homes and gardens. Downing met architect Calvert Vaux in England in 1850 and convinced him to move to America to work with him designing homes on Hudson Valley estates. In his magazine, through which he gained renown as a “tastemaker,” Downing advocated for a large park for New York. In 1852, Downing drowned in a steamboat accident in the Hudson River; had the unfortunate incident not occurred, Downing would have likely been the co-designer of Central Park with Vaux.

Egbert Viele (1825 – 1902)