Seneca Village Q&A

The Conservancy’s research into the history of Seneca Village builds on decades of work, including research and archaeology by the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History (IESVH) and the New-York Historical Society, among many others. We continue to work with our partners to uncover more about the history of the site, but have codified our knowledge into a comprehensive Q&A.

Note on Language: We often use the term African American to describe the African-descended members of Seneca Village, because many Black organizations in the city at the time, including two churches in the village used the term African to identify themselves. The terms “Colored” and “Black” also appeared in census records and on maps in the mid-19th century. Some villagers, however, might have been of mixed African and European and/or Indigenous heritage (as suggested by some census takers), and at least one resident originated in Haiti highlighting the variability of social identity in Seneca Village.

+ How did Seneca Village come to be?

Seneca Village originated in 1825 when free African Americans who lived downtown began buying property in the area between the planned routes of Seventh and Eighth Avenues, from 82nd to 89th Street. (Manhattan’s street grid had been mapped out in 1811, but most of the avenues and streets were not yet laid out in the sparsely developed area this far uptown.) Among the earliest purchasers was the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, an important African-American institution founded in New York City about two decades prior, which initially acquired land for a burial ground. Members of this church and other African-American individuals purchased other plots of land nearby; some rented their property while others lived there, constructing houses, cultivating the land, raising their families, and building the community we now know as Seneca Village.

For the residents who settled in the area, this was an opportunity to create an autonomous community about three miles from the center of population downtown. Although New York State’s gradual emancipation of enslaved people had been underway since 1799, slavery was not abolished until 1827, just two years after the establishment of Seneca Village. Even after Emancipation, Black New Yorkers still faced grave obstacles to freedom and citizenship, ranging from violent attacks to racial discrimination that limited opportunities for work, housing, education, and more. In this sparsely settled region of Manhattan, the community was a refuge from the rampant racism and hostility downtown, as well as from increasingly unhealthy living conditions, as the population of the City grew exponentially, and the City’s old housing stock and meager sanitation system could not keep up.

Learn More

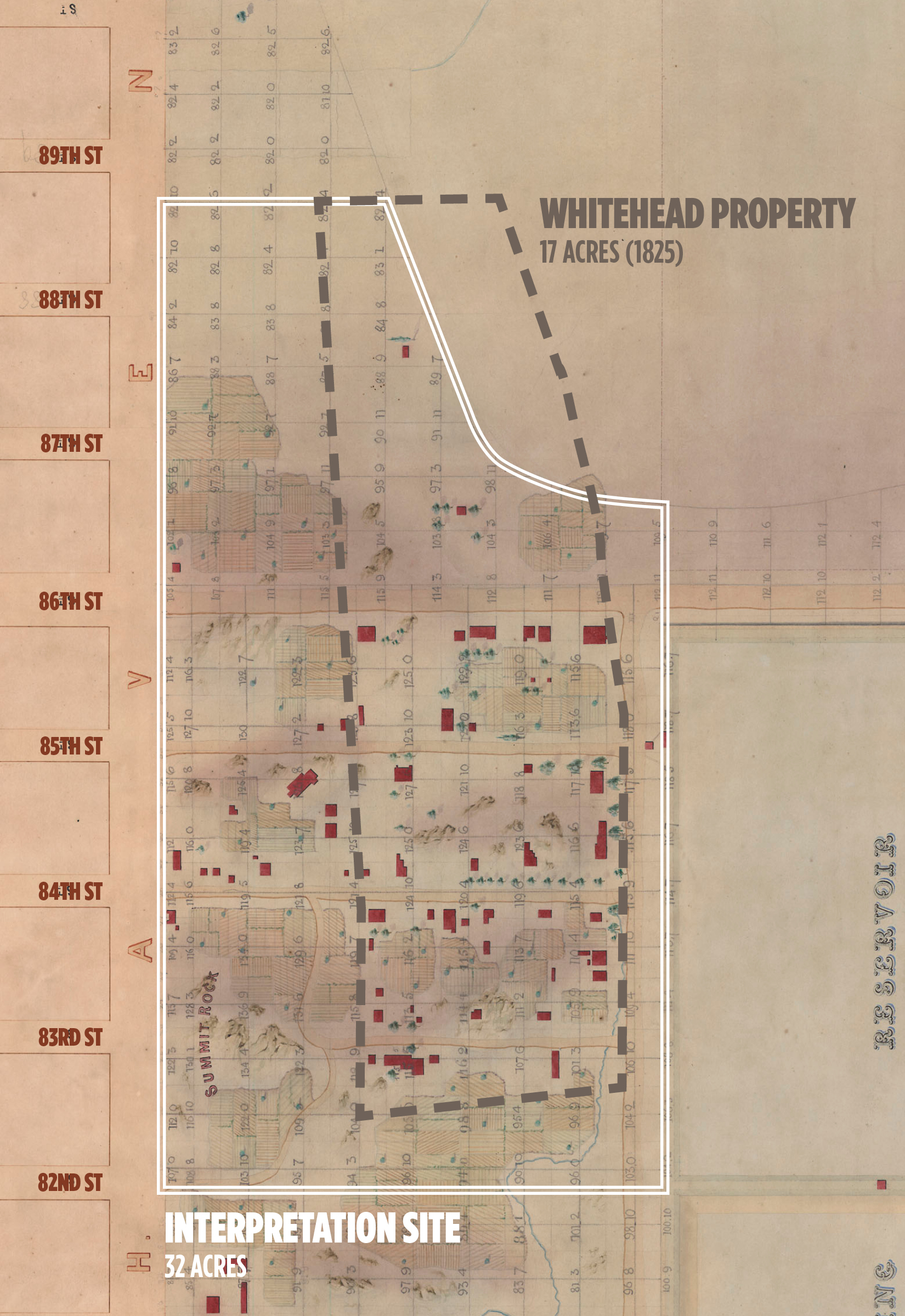

In 1824, John Whitehead purchased 17 acres of property within the future site of Central Park. Whitehead, a prosperous white cartman (that is, a hauler or teamster), divided the land into 200 individual lots and began selling them the following year. For the next decade, he sold off the property solely to African Americans, who established the community known today as Seneca Village. Research suggests that Whitehead was sympathetic and had connections to the African-American community, and that he may have purchased the land for the specific purpose of conveying it to them. In her comprehensive history of the pre-Park site, Sara Cedar Miller describes in detail the succession of property subdivision and ownership leading up to Whitehead’s purchase. (Before Central Park, chapters 8 and 9.)

For a discussion of discrimination and threats faced by Black New Yorkers, from which Seneca Village offered a refuge, refer to “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City” an article by Diana diZierga Wall, Nan A. Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland published in 2008 by the Society for Historical Archaeology.

For more about the history of African-Americans in New York City, see Leslie M. Harris’s

In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City 1626-1863.

+ Who lived in Seneca Village?

For the first half of Seneca Village’s 30-year existence, all of the residents we know of were African American. Irish immigrants began renting in the community in the 1840s. We have the clearest sense of who lived in Seneca Village in 1855 because of a “condemnation map” of all of the private property that was taken to acquire the land that became the Park. Researchers have focused on the portion of this map that documents who owned or rented the lots within Seneca Village, who lived in the community, and the types and sizes of structures that they built, including houses, sheds, barns, stables, a school, and three churches: African Union, AME Zion, and All Angels’ Episcopal. Researchers have used this information in conjunction with deeds, tax records, and the 1855 New York State Census to examine the composition of the community in its final years. The estimated population at that time was 225 individuals, approximately two-thirds of whom were African American, while one-third were of Irish or German descent.

Most Seneca Village residents were employed as skilled and unskilled laborers or service workers, the main occupational categories available to African Americans at the time. Among the occupations listed in the census records for the village’s Black residents are laborer, porter, gardener, cook, waiter, domestic, laundress, sailor, cooper, grocer, barber, preacher, and cartman. Many likely worked in the country estates along the Hudson River in the wealthy enclave of Bloomingdale, or in hotels or businesses in Bloomingdale to the west and the emerging village of Yorkville to the east.

Learn More

In chapter 9 of Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller examines the residents of Seneca Village—who they were, their livelihoods and real estate pursuits, and the interrelationships between members of this relatively tight-knit and stable community. Miller’s work builds upon the research of Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar presented in chapter 3 of their 1992 book, The Park and the People, which restored the memory of Seneca Village to public consciousness and spurred decades of further research and investigation by historians and archaeologists.

Because neither the federal nor New York State censuses recorded addresses before the 1870s, determining who lived in Seneca Village when and where is challenging, and the total population in 1855 can only be estimated. The 1855 “condemnation map” includes names of landowners and renters that can be traced to families documented in the New York State Census of that year. Both the map and the census are imperfect and incomplete records, however, so researchers have looked to other surviving documents—such as city property tax records, municipal death records, and the records of All Angels’ Church—to help resolve discrepancies and gaps. Determining exactly who lived in the village before 1855 is even more challenging.

+ Where else in New York City did African Americans live?

During the 19th century, the City’s African-American population was concentrated downtown, in the fifth, sixth, and eighth wards. (Today these are roughly the neighborhoods of SoHo, Tribeca, the West Village, and Chinatown.) Free and enslaved Blacks had a long presence in the City, dating back to the very beginning of the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam. Although the abolition of slavery in New York State in 1827 inspired great hope for many African-American New Yorkers, significant aspects of their lives were still severely limited by discrimination. Barred from many businesses, institutions, and occupations, when possible, they chose to live near one another and in close proximity to Black schools, churches, and charitable organizations. An area with a substantial population of Black residents called “Little Africa” was located south of Washington Square in the heart of present-day Greenwich Village. Institutions in this area included churches (including the main branches of two of the churches in Seneca Village, African Union, and AME Zion); branches of the Freedman’s Saving and Trust Company (established after the Civil War); and African Free School No. 3, which educated both free and enslaved children.

Seneca Village was one of several African-American communities that were established and able to flourish outside of the urban core in the 19th century. Other examples existed in areas that would be incorporated as boroughs of the City in 1898, including Weeksville in Brooklyn, Sandy Ground in Staten Island, and Newtown in Queens, as well as areas across the Hudson in New Jersey, such as Skunk Hollow. Researchers are only just beginning to uncover important connections that existed between these communities.

Learn More

The article “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City” by Diana diZerega Wall, Nan A. Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland describes and compares Little Africa and Seneca Village in 1850, using information from the 1850 Federal Census.

Weeksville in Brooklyn was an African-American community contemporary with Seneca Village. Founded in the 1830s, it endured and was a refuge for Black New Yorkers during the violence of the Draft Riots of 1863. Weeksville grew to be home to roughly 700 families at its peak. To learn more, visit Weeksville Heritage Center, and/or refer to Judith Wellman’s Brooklyn's Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York.

Carla L. Peterson’s Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City traces the efforts and experiences of members of the Black elite in Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn through the lens of her own family.

Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris’s book Slavery in New York, published in connection with the New-York Historical Society’s 2005–2006 exhibition, discusses African-Americans’ long presence in New York City, including the history of enslavement and freedom, and of Black institutions.

The Historical Society of the New York Courts' article "When Did Slavery End in New York?"

explains the complicated process of gradual emancipation.

+ What was so significant about Seneca Village?

Seneca Village is important for many reasons. It was one of only a few communities in the region founded in the 19th century by African Americans. In 1855, more than half of the African-American households in Seneca Village owned their land. This rate was atypical, and not only in comparison to the rate among Blacks elsewhere in the City. It was also five times greater than the rate of property ownership among all New Yorkers. Even more atypically, several Black women owned land in the village. Many Seneca Village families remained there for more than 15 years, and some were present in the village from its beginning in 1825 to its end in 1857. Villagers cultivated their own land and raised animals for food, making them more self-sufficient and Iess dependent upon city markets or wages to meet their needs. Records also indicate that families in Seneca Village sent their children to school at an atypically high rate compared to those downtown, suggesting that villagers prioritized education and recognized its importance for their families.

Seneca Village was also diverse. African-American heads of house had been born in four different New York counties, eight different states, and one different country (Haiti), according to the 1855 New York State Census. By the 1840s, European immigrants, mostly from Ireland, settled within the village. Some families were large, with multiple children and grandparents and aunts; others were small. Some villagers lived in two- and three-story houses, while others lived in modest one-story dwellings. The village’s three churches and one school anchored social life and strengthened ties within the community. All Angels’ was an integrated church where Black and white members of the congregation worshipped together. AME Zion was a denomination known to have been staunchly abolitionist and involved in the Underground Railroad in other areas of the City, and perhaps in Seneca Village, too. Contrary to disparaging depictions by journalists and others chronicling the construction of the Park in the 1850s—who typically portrayed Seneca Village and other pre-Park settlements through the lens of prevailing racist and anti-immigrant attitudes—the evidence uncovered by researchers defies the characterization of Seneca Village as a community of shanties and squatters.

Furthermore, for New York’s rapidly expanding free Black population, owning property was a path to suffrage. In 1817, New York State established July 4, 1827, as the date by which all enslaved people would be free. But even as the date of emancipation approached, the right of Black New Yorkers to vote was under attack. Prior to 1821, New Yorkers were eligible to vote regardless of race, provided they were male and free, and they met certain property ownership requirements. In 1821, the legislature passed a law requiring African-American men to own at least $250 worth of property to vote, while repealing a lesser requirement for white men. By this time, the population of free Blacks in the City had surpassed 10,000—about 95% of the Black population—but very few met the requirements to be able to vote. (It’s not known exactly how many were eligible, but in 1826, a year after the inception of Seneca Village, only 16 Black New Yorkers cast a vote.) For many Seneca Village landowners who did not live in the community, property was not only a financial investment—it was also a means of securing the right to vote and attaining political power.

Learn More

Leslie M. Harris’s In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 examines the long history of African-Americans in New York City, the complexities of New York’s reckoning with slavery, and the implications of its gradual process of emancipation.

In chapter 9 of Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller discusses the role of property ownership in Seneca Village in the enfranchisement of African-Americans in antebellum New York. Chapter 10 discusses the non-resident community of Seneca Village property owners, who were among the City’s most highly respected civic leaders and entrepreneurs.

Brent Staples’s article “The Lost Story of New York’s Most Powerful Black Woman” discusses the extraordinary life of Elizabeth Gloucester, who had been born into slavery and became one of the wealthiest Black women in the country, in part through her astute real estate investments, including property in Seneca Village.

Cheryl Janifer LaRoche’s book Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance surveys Black communities from the Midwest to the East Coast that were stops on the Underground Railroad and discusses the important role of Black churches and their leaders in helping people reach free states to escape enslavement, and to avoid kidnapping by “blackbirders” hired by enslavers.

+ What did Seneca Village look like, and what was it like to live there?

There are no known photographs or illustrations of Seneca Village or firsthand accounts of what it was like to live there. Some photographs that exist from the 1850s show dwellings in the vicinity and the nearby landscape before it was transformed into Central Park, but they do not depict Seneca Village specifically. A team of researchers has developed a digital project, Envisioning Seneca Village, to help us better imagine what the village looked like based on the available information. They drew upon research by many other scholars, and conducted new research. Key sources include historic maps and surveys, letters written by villagers to the City challenging the assessed value of their property, a photo of All Angels’ Church after it was dismantled and relocated to the Upper West Side, and findings from the 2011 archaeological excavation in the village, as well as general research into the history of vernacular architecture and daily life in rural areas in the 19th century. The historic maps tell us a lot about the layout of the village, including the distances between homes and other structures and the locations of planted fields and orchards. Three churches, a school, and some of the larger homes were located in the heart of the community, near present-day 85th Street. The village was concentrated between what would be 83rd and 86th Streets, with the property to the north largely used for agriculture and one of the village’s four cemeteries. Rising above the village to the southwest was the unoccupied high ground of Summit Rock, and just beyond, a natural spring served as a source of drinking water for the community.

When the first residents settled in the village, the land to the east (between the mapped lines of Seventh and Sixth Avenues—the present-day site of the Great Lawn) was common land owned by the City of New York. Between 1838 and 1842, the receiving reservoir of the Croton Aqueduct system was constructed on this site. The rectangular, 35-acre structure would have been a commanding presence along the eastern edge of the community. Most homes in the village were one or two-story wood-frame houses (several were two and a half or three stories). Many had sheds, barns, or stables that supported the agricultural activities of the villagers. Archaeological excavations have revealed that at least some of these houses had substantial stone foundations and metal roofing, indicating that they were well built. Artifacts discovered during excavation—including stylish ceramic dishes, combs, a toothbrush, pencils, fashionable buttons, and medicine bottles—suggest that families were able to purchase more than the bare necessities, and that many residents were concerned with how they presented their homes and bodies and participated in then-new middle-class fashions and ideas about hygiene.

Learn More

Envisioning Seneca Village, a digital project created by Gergely Baics, Meredith Linn, Leah Meisterlin, and Myles Zhang, presents a 3-D model of what Seneca Village might have looked like in 1855.

Findings and analysis of archaeological investigation of the site by the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History are available on the website of the NYC Archaeological Repository. An online exhibit of the artifacts is also available on the Landmarks Preservation Commission website.

In chapter 13 of Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller tells the history of building the receiving reservoir and the Seneca Village residents and landowners who were affected by the reservoir.

For more about what the artifacts uncovered in the 2011 excavation might say about how Black Seneca Villagers thought about their identities as African-Americans, see Diana diZerega Wall, Nan A. Rothschild, and Meredith B. Linn’s chapter "Constructing Identity in Seneca Village" in Archaeology of Identity and Dissonance: Contexts for a Brave New World, edited by Diane F. George and Bernice Kurchin.

+ Where does the name “Seneca Village” come from?

The origin of this name is unknown. No record of its use at the time the community existed has been found, and historians do not believe it was ever used by the residents or their immediate descendants. The earliest known instance of the community being referred to as “Seneca Village” is in a publication by Thomas McClure Peters in 1873, more than 15 years after its demise. Peters had been an assistant priest (and later rector) of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church on the Upper West Side, and he started a mission in Seneca Village and then established All Angels’ Church. His son, the Reverend John Punnett Peters, carried forward the use of the name in a history of St. Michael’s published in 1907, and in which he described the community in mostly derogatory terms.

Various possible explanations have been put forth as to the origin of the name. Given that contemporary descriptions generally maligned the community using racist language, one theory is that the name refers to the Indigenous Seneca Nation of western New York and was intended as a slur against another non-white community. Some speculate that if the name originated in the African-American community, it might have been chosen for uplifting associations, possibly including a reference to Seneca Falls in upstate New York and the abolitionist movement there, or to the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, whose anti-slavery book Morals inspired many African-American activists. In her recent book Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller offers an intriguing theory: Egbert Viele, the engineer-in-chief responsible for surveying the Park site, prepared and promoted a plan for the Park that ultimately lost out to Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s design. We know from a journalist’s account that Viele intended to name the Park’s roads and drives for the counties of New York, “preference being given to Indian names.” It is likely that Viele would have contemplated naming a road for the Seneca—one of five tribes that made up the prominent Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy—and it’s possible that this is the origin of the name “Seneca Village.”

Learn More

In Before Central Park,, Sara Cedar Miller discusses the possible origins of the term “Seneca Village” to refer to the community.

In her book African or American? Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784-1861, Leslie M. Alexander proposes the name Seneca Village might have referenced the Roman philosopher Seneca. (See pages 222–223.)

+ Is there a history of Indigenous people inhabiting the pre-Park site?

Historians are not aware of any Indigenous settlements on the land that became the Park, and archaeologists so far have not found any conclusive material remains. Settlements and campsites were generally located closer to the Hudson and East Rivers, but Indigenous people would have hunted and gathered on the site, and their trails passed through its northeastern region. The old Kingsbridge (or Eastern Post) Road—which entered the site at what would become Fifth Avenue and 92nd Street and traveled through a narrow gap in the rocky bluffs overlooking the Harlem flats—followed the line of the 14-mile Wickquasgeck path used by Indigenous Munsee speaking Lenape people to reach their settlements at the southern end of the island from their campsites to the north.

Learn More

In Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller describes the topography of Manhattan and its occupation by Indigenous people prior to its settlement by the Dutch in 1625. (See introduction to Part 1: Topography.)

Eric W. Sanderson’s book Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City is a detailed study and reconstruction of what the landscape and environment of Manhattan was like in 1609, when Henry Hudson’s ship arrived. See also the New York Botanical Garden’s online Welikia Project, which considers the environment of all five boroughs in 1609.

+ How did the City decide upon the site for Central Park? Was Seneca Village intentionally targeted for removal?

In the 1840s, influential and civic-minded New Yorkers began to campaign for the need to set aside public open space for residents of the rapidly growing city. These early advocates campaigned for a large open space that would provide an escape from crowded urban conditions—a place for New Yorkers to congregate, breathe fresh air, and experience nature. Many saw this effort as an essential measure to improve public health, as a series of epidemics ravaged the City, and to build a great American city that rivaled leading European cities, such as London and Paris. The idea for the park gained support, and by 1851 the City was planning to purchase a 150-acre tract of forested land on the East River, known as Jones’ Wood, as the site for the park. The choice of location hit a roadblock, however, when the prominent Jones/Schermerhorn family that owned the property resisted selling it. Park advocates, meanwhile, objected to the site on the grounds that it was neither large enough nor central enough to meet the objectives of a park meant to serve as a refuge and breathing space for all New Yorkers.

The City began to consider a much larger tract of land in the center of the island that already included a major piece of public infrastructure: the Croton Receiving Reservoir, completed in 1842 to deliver fresh water to the City from the Croton River in Westchester, 38 miles away. The rugged and rocky character of the landscape would make it difficult and costly to develop as real estate, and the area encompassed many acres of common land already owned by the City—all of which would make acquiring the site less expensive per acre. In 1852, a committee charged with evaluating both sites concluded, due to the topography, that it would be far less expensive to develop the central site as a park than to extend the street grid through it, and that the potential for developing it as a scenic landscape made it the ideal site. The size and central location of the site were also factors in the committee’s financial analysis, because it offered greater potential to offset the cost of acquiring the land by levying assessments on surrounding property. There is no evidence that the City or State’s decision on the park location was influenced by an interest in destroying Seneca Village. However, many journalists and others writing in favor of the central location did portray the whole site as a wasteland, and those living on the site as impoverished squatters, without acknowledging Seneca Village as an established and thriving community. And no consideration was given to carving out the few blocks at the heart of the village from the park site to spare its destruction.

Learn More

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Creating Central Park, written by Morrison H. Heckscher, includes an informative and concise discussion of the selection of the site. (See “The Decision to Build a New Park and the Selection of Its Site,” pp. 11–17.)

Sara Cedar Miller’s Before Central Park discusses this subject in detail based on a thorough examination of primary sources. (See chapters 15 and 16.)

+ What was the site of the Park like before it became the Park, and who else lived there?

In the 1850s, most of Manhattan above 50th Street was still relatively sparsely settled. The grid plan had been established in 1811, but only a few major uptown thoroughfares—including Eighth Avenue and 86th Street—had been constructed this far north. The land within the pre-Park site was characterized by rugged and hilly topography with massive rock outcrops and low-lying marshland, and much of it had been deforested. A 35-acre receiving reservoir occupied the site between the mapped lines of Sixth and Seventh Avenues from 79th to 86th Street, and a second, larger reservoir was planned immediately to the north (today’s Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir). The old Kingsbridge (or Eastern Post) Road entered the site at what would become Fifth Avenue and 92nd Street and traveled through a narrow gap in the rocky bluffs overlooking the Harlem flats, on its way to the Bronx, where it split into the Boston and Albany Post Roads.

It has been estimated that about 1,600 people lived on the roughly 800 acres that would become the Park (though the basis for that estimate is not entirely clear, and researchers continue to examine the fragmentary archival record in an effort to make it more precise). The pre-Park population was scattered across farms and homesteads throughout the site, and in a few areas with larger concentrations of residents. Seneca Village was the most densely-settled and the most well established as a self-sufficient community with its own institutions. A community of German immigrants farmed the land that would become the North Meadow and East Meadow. The southern part of the Park site was home to smaller settlements of Irish and German immigrants, some of whom had small gardens and piggeries. In this area were also several small industries, including tanneries and bone-boiling establishments. The pre-Park site was also home to a few estates of wealthy New Yorkers and to the Sisters of Charity, a Roman Catholic order of nuns founded in Maryland in 1809 and dedicated to serving the poor. They purchased a former colonial-era tavern along the Old Kingsbridge Road at the north end of the Park and established Mount St. Vincent, which included their convent and boarding school for Catholic girls.

Learn More

Before Central Park,by Sara Cedar Miller, offers a history of the pre-Park site from pre-colonial times through the Dutch and English colonial era, through the Revolutionary era, to antebellum New York (including the establishment of Seneca Village and other settlements on the site). Her work builds upon the research of Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar for their 1992 book,The Park and the People, which restored the memory of Seneca Village to public consciousness and spurred the decades of further research and investigation by historians and archaeologists that followed. (Seneca Village is covered in pages 66–73.)

For more information about the fascinating history of the City’s grid plan, see the Museum of the City of New York’s interactive website “The Greatest Grid” and Hilary Ballon’s book The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011

+ How did the City acquire the land for the Park from property owners?

In 1853, the City was authorized by an act of the New York State Legislature to buy the land for Central Park using the power of eminent domain, which gives the government the authority to force the sale of private property for public use. The Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution stipulates that the government may only exercise this power if it provides “just compensation" to the property owners. Eminent domain has historically been used by government entities to acquire private property for a range of purposes, including military uses, roads and street systems, schools, hospitals, and urban infrastructure. For many New Yorkers, eminent domain has come to be closely associated with Central Park, but it was far from the most extensive application in New York City. Private property taken for the implementation of Manhattan’s street grid affected property owners of all backgrounds as the 1811 grid plan was extended uniformly and indiscriminately northward, from Houston Street up to 155th Street. The Croton Aqueduct system, constructed to supply drinking water to the City, is another example of a project for which property was acquired through eminent domain, displacing far more people than the Park. With the creation of Central Park, New York became the first city in America to identify the need for recreational open space as essential infrastructure necessary to support public health and sustainable growth of the city, and to use eminent domain for this purpose.

While eminent domain has been—and continues to be—an important and necessary means of enabling government to perform vital functions on behalf of the community at large, scholars and advocates have long recognized that its use has disproportionately impacted disadvantaged communities and people of color, who have historically lived in areas with lower property values and have had less access to recourse. This inherent degree of inequity was exacerbated in the 1950s by a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that expanded the definition of “public use” to include “public benefit,” paving the way in the decades that followed for “slum clearance” programs that targeted low-income neighborhoods and communities of color for redevelopment by declaring them blighted. Displacement by eminent domain can have myriad negative downstream effects, including loss of community and often the loss of the ability to own property anywhere nearby, as the compensation offered does not factor in increases in adjacent property values after development. The alarming wealth gap between Black Americans and white Americans today is largely a direct result of the barriers Black Americans have historically faced in owning property, which severely limits opportunities to form stable communities and participate in activities that are critical for upward mobility and intergenerational prosperity.

Learn More

In Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller discusses the implementation of Manhattan’s grid plan as New York City’s most sweeping and impactful use of the power of eminent domain, which was also used to acquire the land for Central Park.

For a discussion of how the inconsistent application of eminent domain has impacted civil rights, read the 2014 report of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights entitled The Civil Rights Implications of Eminent Domain Abuse: A Briefing Before The United States Commission on Civil Rights Held in Washington, DC.

+ Were Seneca Village residents fairly compensated for their land?

Condemnation maps compiled in 1856 reveal the information that was used to determine who and how much would be paid for all property taken for the Park. As a rule, corner lots and those on the avenues were more valuable; characteristics of the land and the size and quality of the structures on the land did not factor into property values as much as location did. Researchers examining the compensation paid to owners of property throughout the Park site have not found any inconsistencies between how property in Seneca Village was assessed as compared with the rest of the site. The research suggests that, with only slight exception, property owners received fair market value—that is, the “just compensation” stipulated in the Constitution—for their property.

In any case, surviving letters of affidavit to the City show that many property owners—including some in Seneca Village—contested the City’s valuation of their property and petitioned for a higher price. The letters detail information such as the original price they paid for the property, the cost of improvements they had made, and/or offers to purchase their land that private individuals had made to them previously. William Mathews, a resident of Seneca Village and preacher at the African Union Church listed the amount of money he had invested in building his house, digging a well, planting trees and shrubs, and raising the property to street grade. John Wallace, an Irish-born assistant reservoir keeper, also noted the unquantifiable value of his home in a letter to the City that many residents likely would have identified with, stating “although comparatively worth less to the authorities of the park, it is to me of considerable importance, having a wife—and four little children to support.”

Learn More

In Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller discusses how the land authorized by the State of New York to be taken for the Park through eminent domain was surveyed and valued to determine compensation. (See chapter 16.)

+ Were people forcibly or violently removed from the site?

The site for the Park officially became the property of New York City in February of 1856 when the state supreme court, after hearing objections and petitions filed by landowners and others, approved the assessors’ report and the owners (and some renters) were paid their awards. Many left the site at that time; others remained as tenants of the City of New York as late as October 1857, when the funding to construct the Park was in place, and the remaining residents were evicted. Nothing in the research that the Conservancy and colleagues at other institutions have conducted since the early 1990s, when the historians first rediscovered the history of Seneca Village, has suggested that any physical conflict occurred in connection with the taking of the property. That said, being forced to leave their homes and their haven must have been devastating for longtime residents, many of whom were founders of the community.

Learn More

In The Park and the People, based on accounts from primary sources, Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar describe the evicted residents of the Park leaving “quietly and without violence.” Rosenzweig and Blackmar also discuss subsequent secondary accounts of police being called in to evict pre-Park tenants, which they attribute to possible confusion between the taking of the parkland and subsequent raids, two years later, on piggeries near the Park’s western boundary.

+ What happened to the residents of Seneca Village when the City acquired the land for Central Park? Where did they go?

After they were forced to leave, Seneca Village residents dispersed to other parts of the City and elsewhere. Researchers have been working to trace their journeys and locate descendants. One resident whose story has been rediscovered is Andrew Williams, a bootblack and cartman who was a member of the AME Zion Church and one of the first individuals to purchase property in Seneca Village. He and his family remained in the community until the end. After leaving Seneca Village, he moved to Queens, where he was able to reinvest the money received for his property in a new home. Williams is the first resident whose living descendants have been located.

Elizabeth Harding McCollin, another original resident, moved with her husband Obadiah McCollin to First Avenue and East 85th Street. Elizabeth had been the first woman to purchase property in Seneca Village, and she later purchased additional lots with her husband. With the profits earned on her Seneca Village property and subsequent real estate investments, she left generous bequests to charitable causes as well as several close relatives and friends.

William Godfrey Wilson, who as sexton for All Angels’ Church was responsible for maintaining the building and yard, had lived with his wife and eight children in a house adjacent to the church. More is known about the Wilson household than about most residents in Seneca Village, thanks to the discovery by archaeologists of their home’s foundation and numerous artifacts providing more insight into the family’s daily life and seemingly middle-class identity. After the land for the Park was taken, All Angels’ moved the building to 11th Avenue between 80th and 81st Streets, and the Wilson family moved to the Upper West Side, near the new location.

Learn More

In Before Central Park,Sara Cedar Miller traces the paths of several Seneca Village residents after they were forced to leave.

For more about the Wilson family and artifacts uncovered in the remains of their home in the 2011 excavation see Diana diZerega Wall, Nan A. Rothschild, and Meredith B. Linn’s chapter “Constructing Identity in Seneca Village” in Archaeology of Identity and Dissonance: Contexts for a Brave New World, edited by Diane F. George and Bernice Kurchin.

+ Are residents of Seneca Village still buried on the site?

As is typical of burials that existed on land developed in this period of NYC history, little archival documentation exists with respect to what happened with most of the burials on the pre-Park site. We do know that the Board of Commissioners of Central Park were aware of burial grounds on the site, and in January 1858, they authorized the superintendent of the Park to permit the removal of the remains of people buried in the Park. The burials for three Jewish congregations in the pre-Park, in the vicinity of the Reservoir and the Conservatory Garden, were removed to cemeteries in Queens. Research into the records of Protestant cemeteries in Queens and Brooklyn shows that two of the churches in Seneca Village began using them after 1852, when the City banned burials below 86th Street. Researchers believe it is possible that some of those burials were reinterments from Seneca Village.

Several ground-penetrating radar studies conducted in connection with archaeological investigation of the Seneca Village site identified what appear to be grave sites in the vicinity. Assuming they are, in fact, grave sites, it is not possible to know for certain whether they still contain remains, or if they were reinterred. The only way to confirm would be to conduct excavations, which is not the recommended practice per the City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), the agency that regulates all archaeology on parkland. LPC’s guidelines discourage archaeological excavation to identify suspected remains and call for monitoring and protection during activities that might disturb any such remains. For the archaeologists who have long worked to learn more about residents of Seneca Village, avoiding disturbing any burials has been an ethical issue of the highest priority.

Learn More

The New York City Cemetery Project website hosts an impressive amount of research on the history of cemeteries in New York City, including the displacement of early cemeteries by development and what we know about whether or not remains were reinterred.

Prepare for Death and Follow Me: An Archaeological Survey of the Historic Period Cemeteries of New York City by Elizabeth D. Meade, a CUNY Grad Center PhD in anthropology, is a comprehensive history and analysis of historic New York City cemeteries. Meade has also created an interactive map: "The Cemeteries of New York City"

In chapter 14 of Before Central Park, Sara Cedar Miller discusses the burial grounds on the pre-Park site.

For more about the 2011 Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History (IESVH) archaeological project and how it has approached the study of the village, including purposely avoiding disturbing burials, see Meredith B. Linn, Nan A. Rothschild, and Diana diZerega Wall’s chapter “Seneca Village Interpretations: Bringing Collaborative Historical Archaeology and Heritage Advocacy to the Forefront and Online” in Advocacy and Archaeology: Urban Intersections, edited by Kelly M. Britt and Diane F. George.

+ Who were the Lyons family and what is their connection to Seneca Village?

Albro and Mary Joseph Lyons and their children were a prominent and pioneering African-American family who made notable contributions to their community and social justice. They were also property owners who held land in Seneca Village, which Mary Joseph Lyons had inherited from her parents, Joseph and Elizabeth Marshall. Albro Lyons was a successful businessman, civic leader, and noted abolitionist. The family ran a boarding house for African-American sailors downtown (first on Pearl Street and later on Vandewater Street) that was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Their home was destroyed by a mob during the draft riots of 1863, after which the family relocated to Providence, Rhode Island. They returned to the New York area a few years later, and their daughter Maritcha enjoyed a 60-year career as a public school teacher and principal in Brooklyn. She was also a leading activist for desegregated education and women’s rights.

Their prominence in New York City history, as well as the fact that they are among the Black New Yorkers of the era of whom we have photographic portraits, amplifies the attention that the Lyons family’s connection to Seneca Village has received, though they did not live in Seneca Village, and there is no evidence that they spent time there. Members of St. Philip’s Protestant Episcopal Church downtown, the family initially resided nearby on Centre Street before moving into the boarding house they ran on Vandewater Street. Mary and her sister, Rebecca Guignon, had inherited the six lots in the village that her father, Joseph Marshall, had purchased from John Whitehead in or around 1826. Like many Seneca Village landowners who lived downtown, they may have purchased their pre-Park property as an investment and path to suffrage, and to support the community at large. Their connection to Seneca Village underscores how, despite the settlement’s geographic remoteness, it played a central role in the political and social history of African Americans in antebellum New York.

Learn More

In her discussion in chapter 10 of Before Central Park about the City’s Black leaders and entrepreneurs who owned property in Seneca Village, Sara Cedar Miller traces the story of the Lyons family’s ascendance and their legacy.

The Lyons family is featured in the Museum of the City of New York’s exhibit Black Activists of 19th Century NYC.

Carla L. Peterson’s Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City traces the efforts and experiences of members of the Black elite in Lower Manhattan and Brooklyn through the lens of her own family, which include the Marshalls, Guignons, and Lyonses.

+ How big is the site of Seneca Village?

Because the community known today as Seneca Village was not incorporated and defined by legal or official boundaries, the answer to this question requires some interpretation and depends upon what is considered important and relevant to our understanding of the site. The inception of Seneca Village was the sale of lots by a single property owner, John Whitehead, who in 1825 subdivided a 17-acre parcel he had purchased a year earlier and sold the lots exclusively to African Americans in the decade that followed. The property subdivided and sold by Whitehead lay roughly between 83rd and 89th Streets, extending west of the City-owned common lands (at the hypothetical Seventh Avenue), about halfway to Eighth Avenue. Settlement was concentrated in the southern portion of the Whitehead property, with the land north of 86th Street supporting agricultural uses and largely undeveloped, although one of AME Zion’s burial grounds was also located north of 86th Street. Over time, the community expanded west toward Eighth Avenue, and the core, settled area came to occupy the approximately 15 acres between 83rd and 86th Streets.

For the purposes of interpretation, historians generally define the Seneca Village site as the nearly 35 acres bound by the lines of Seventh and Eighth Avenues from 82nd to 89th Street. It includes the historically agricultural land north of 86th Street, as well as Summit Rock and Tanner’s Spring—enduring natural features that would have been a vital part of community life, and that play a key role in helping us envision the landscape experienced by Seneca Village residents.

Learn More

+ Is there a connection between Seneca Village and the Underground Railroad?

While researchers have not found any direct evidence that Seneca Village was a stop on the Underground Railroad, the village’s location far from the center of population downtown, and in a much less developed area, could have been helpful for hiding fugitives. In addition, the AME Zion and African Union churches were both closely connected to the abolitionist movement and likely involved in the Underground Railroad.

The boarding house Albro Lyons and his family-owned downtown was a noted stop on the Underground Railroad. Maps and other records indicate that no buildings were constructed on their Seneca Village land, so an Underground Railroad stop there seems unlikely. That said, many ardent abolitionists and leaders in the Underground Railroad movement owned or paid the taxes on property in Seneca Village—most notably Elizabeth Gloucester, Reverend Theodore S. Wright, and Reverend Charles B. Ray—so there may have been plans afloat and ties with the community.

Learn More

Sara Cedar Miller’s discussion of the City’s Black leaders and entrepreneurs who owned property in Seneca Village in chapter 10 of Before Central Park describes the connection of several to the Underground Railroad.

Cheryl Janifer LaRoche’s book Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance surveys Black communities from the Midwest to the East Coast that were stops on the Underground Railroad and discusses the important role of Black churches and their leaders in helping people to free states to escape enslavement and to avoid kidnapping by “blackbirders” hired by enslavers.

For more about sites of abolition and the Underground Railroad in NYC, see the Landmark Preservation Commission’s story map New York City and the Path to Freedom.

+ What work has the Central Park Conservancy done in connection with Seneca Village?

The Conservancy’s work related to Seneca Village is grounded in our research as part of the planning process for restoration of the Park in the early 1980s, which included mapping the structures and natural features of the pre-Park site. In the mid-1990s, we conducted historic research and archaeological investigation of the Seneca Village site specifically, in connection with the restoration of the Great Lawn. The Conservancy facilitated archaeological investigation of the site conducted by the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History (IESVH) in 2011, and we engaged our archaeological consultant, Hunter Research Associates, to conduct archaeological investigations between 2015 and 2021 in order to assess and prevent any potential impacts in connection with planning for renovation and reconstruction of two playgrounds in the area.

In 2019, the Conservancy installed Discover Seneca Village, an outdoor exhibit created in collaboration with the IESVH and Hunter Research, Inc., in the Park landscape that is the site of Seneca Village. Signs at 16 locations throughout the site mark the locations of the village’s churches and other buildings, provide information on residents, and highlight current features in the landscape that existed in Seneca Village. It was important to the Conservancy to share this information in the context of the Park landscape, to help visitors interpret the site, visualize the village, and appreciate its significance in the place where the residents of Seneca Village actually lived.

Most recently, the Conservancy has provided support for Envisioning Seneca Village, a digital project including a 3D interactive model of what Seneca Village might have looked like in 1855, created by Gergely Baics, Meredith Linn, Leah Meisterlin, and Myles Zhang.